The post Company K First Alabama Regiment – THREE YEARS IN THE CONFEDERATE SERVICE CHAPTER VII appeared first on Digital Alabama.

]]>THREE YEARS IN THE CONFEDERATE SERVICE CHAPTER VII

EXPERIENCES OF PAROLED PRISONERS OF WAR

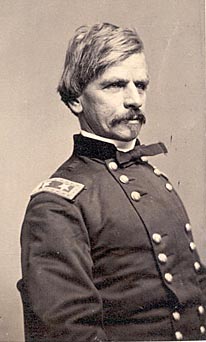

Nathaniel Prentice Banks was an American politician from Massachusetts and a Union general during the Civil War. A millworker by background, Banks was prominent in local debating societies, and his oratorical skills were noted by the Democratic Party.

During the negotiations for the surrender, Gen. Banks refused to grant terms permitting the release of the prisoners on parole, on the ground that orders from Washington positively forbade it. On the day of surrender, however, he suddenly changed his mind and decided to parole all enlisted men, retaining the officers.

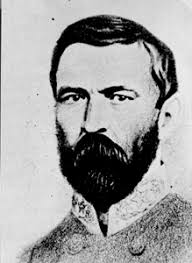

Richard “Dick” Taylor was an American planter, politician, military historian, and Confederate general. Following the outbreak of the American Civil War, Taylor joined the Confederate States Army, serving first as a brigade commander in Virginia, and later as an army commander in the Trans-Mississippi Theater.

Gen. Dick Taylor’s capture of Brashear City, and his nearly succesful attack on Donaldsonville, threatening communication with New Orleans, may have had some influence in causing the change of purpose.

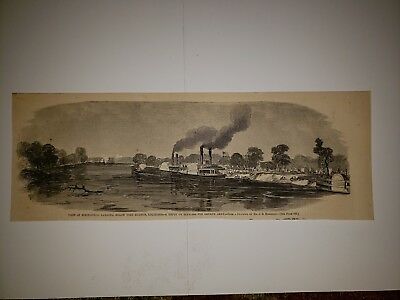

William Wirt Adams was a banker, planter, slave-owner, state legislator, and Brigadier-General in the Confederate States Army.

Gen. Wirt Adams’ audacious dash into Springfield Landing and his destruction of a large amount of commissary supplies stored there, seriously embarrassing the Federal commander in feeding his own troops, also made the paroling of the prisoners advisable. There is no doubt, however, that Gen. Banks was influenced by an honest admiration of the gallantry and fortitude of the garrison, and this was his avowed reason for paroling them. Blanks were at once printed, Private J. C. Rogers, of Co. K, acting as the printer, and on Saturday, July nth, the giving of the paroles began.

Springfield-Landing-Port-Hudson-Civil-War

The paroling of the First Alabama was completed Tuesday forenoon (the 14th), and in the afternoon the regiment, with the exception of those in the hospitals, bade farewell to their officers and marched out of the fortifications. Of Co. K, but one was left behind—James Herndon, who died a few days later. Altogether, about 500 enlisted men of the garrison were left behind in the hospitals, sick and wounded.

A DISORGANIZED REGIMENT

The regiment kept well together till they were fairly outside the enemy’s lines, and then, in the absence of the commissioned officers, all organization was at an end. About eight miles from Port Hudson the main body of the regiment encamped, but some of the men marched on, and all through the night squads were leaving. No attempt was made in the morning to keep the men together. Maj. Knox, who escaped, and who joined the regiment after it was outside Gen. Banks’ lines, rode forward to secure rations for the regiment, but failed, and we did not see him again till we reached Shubuta, where he made arrangements for our transportation to Mobile.

Most of Co. K, and of the First Alabama, took the direct road to Shubuta, a station on the Mobile and Ohio Railroad. At Clinton Privates J. H. Byrd and A. J. White went to the hospital, where both died on July 25th.

The writer can only give the experiences of a party of eight, of which he was one, on the homeward trip, but all probably fared about alike. Our party consisted of Orderly Sergt. Cameron, Sergt. Fay, Corp. Blaylock, Privates Bledsoe, Hurd, Lamar and Smith and a youth named Dennis, who was with the company but not mustered in. On the second day after leaving Port Hudson, members of the squad purchased a horse, mule and Jersey wagon, with which to carry our baggage and sick.

CLOSE QUARTERS

The wagon had well-worn wooden axles which constantly broke; the horse was sore back and skeletonized, but the mule was a very fair animal. With this team we left Clinton on the morning of the 16th, but just before night halted for repairs, having made fifteen miles. On Friday, the 17th, after the wagon had been overhauled at the wayside smithy, we marched to Tangipahoa, eighteen miles. Two of the party, with the wagon, left early the next morning for Summit, Miss., while the others remained at Clinton till Sunday afternoon, and then took the train on the N. O. & J. Railroad, arriving at Summit at 9, p. m. So soon as we got off the Confederate cavalry burned the train, to prevent it falling into the hands of the enemy. The wagon detail arrived just before the train, having broken down on the road, necessitating the making of two axles.

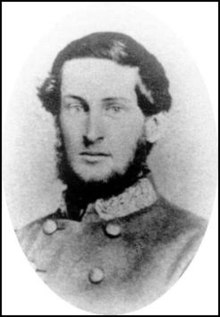

Thomas Muldrup Logan was an American soldier and businessman. He served as a Confederate general during the American Civil War, and afterward was greatly involved in railroad development in the Southern United States.

On Monday morning we started due east for Monticello, and camped after marching twenty-two miles. At 11, a. m., Tuesday, we reached Monticello, where we found Gen. Logan’s command (Confederate) crossing Pearl River. At Tangipahoa we drew rations, and at Monticello Gen. Logan’s commissary honored Sergt. Cameron’s requisition. From Monticello we took the Williamsburg road through the piney woods, scoring for the day twenty-one and one-half miles. Now began daily skirmishes for something to eat, as those who were ahead of us had cleaned the section adjoining the road like a cloud of locusts—there was little left to beg, buy or steal. On Wednesday we scored nineteen and one-half miles, dining, for a consideration, with a probate judge. A shower coming up, we stopped at dusk one mile west of Williamsburg at a log cabin—one room and a shed. The family consisted of a man, his wife, two sons and two daughters. The paroled soldiers who had been passing for two days had nearly drained them of everything, but they treated us very cordially, gave us supper and breakfast of cornbread and bacon, and spread us a pallet of quilts across the floor in front of the fire. With difficulty could they be induced to accept even a trifling compensation. In addition to our party of eight, there were three other soldiers. The lady (poor and ignorant, she was a lady) occupied the shed room with her two daughters, while the host, his two sons and eleven guests slept in the main room. It was our experience all along the route that, while there was no cause of complaint against any, the poor were the more hospitable. Friday night our party went supperless to our blankets in a roadside camp.

Saturday afternoon we arrived at Shubuta, where we found collected a large number of the paroled prisoners awaiting transportation. It was about midnight when the train going south came along. As it was already full to overflowing, those at Shubuta had to climb to the second deck and take passage upon the roofs of the freight cars. It was a ticklish position, but we lay down, secured ourselves as best we could and went to sleep. At 9, a. m., Sunday, the train arrived at Mobile, and the smoke and dust begrimed deck passengers of Co. K wandered down to the river and performed ablutions in rain water collected in a lot of iron salt-boilers lying on the wharf. At 1, p. m., we took the train for Montgomery, whence the members of Co. K soon made their way home.

A FAITHFUL SERVANT

As illustrating the faithfulness of the negro, it is worthy of record that Lamar’s colored boy Floyd, who was with him at Port Hudson, and who soon after the surrender was missing, was awaiting his master with a horse at Washington Landing. He had got into a fight with a Federal negro soldier, knocked him down and then fled, fearing that he would be conscripted into the Federal army, and had made his way home.

John Tarleton died on his way home, near Monticello.

Seven men, Jesse Adams, M. Deno, Haley, M. Hern, Merritt, J. Schein and J. Shoals never afterwards reported to the company : Jesse Adams was known to have made his way to Mobile.

The other members of Co. K succeeded in getting to their homes, where they remained, enjoying a well earned furlough, until Oct. 12, 1863, when the First Alabama was ordered to report at Cahawba, Ala.

A HANDSOME TURNOUT

Of Co. K, according to such imperfect records as the writer has at his command, the following men reported at Cahawba, or soon after at Meridian, Miss.: Orderly Sergeant, Norman Cameron, J. L. Alexander, E. L. Averheart, O. M. Blaylock, J. Boggan, T. M. Boggan, G. R. Bledsoe, C. W. Brown, Wm. Douglass, Wm. Dubose, George M. Durden, J. Durden, W. L. Ellis, W. H. Fay, W. Farmer, Henry Fralick, P. G. Golsan, John Gorman, John Griffin, J. Hamilton, J. C. Hearn, G. W. Hearn, E. Hearn, Joseph Hurd, W. H. Hutchinson, E. Jenkins, J. Killough, V. Kirkpatrick, M. D. Lamar, E. Leysath, J. Lewis, G. F. Martin, J. W. May, Wm. Moncrief, J. Owens, James D. Rice, Junius Robinson, C. H. Royals, G. H, Royals, E. T. Sears, J. H. Shaver, J. L. Simpson, D. P. Smith, A. C. Smyth, A. J. Thompson, John S. Tunnell, Josiah Tunnell, Wm. Vaughn, John Williamson and T. A. Wilson. J. J. Stuart and J. P. Tharp reported not very long after, and R. H. Kirkpatrick was received as a recruit, total 53. There were absent at the hospitals or invalided: R. H. Callens, at Selma, and J. Hays, at Montgomery, both of whom soon after died; S. Glenn, J. C. Rogers, B. L. Scott and F. Wilkins all of whom soon after received discharges for disability. Clark had been transferred to the navy during the summer.

The officers of Co. K, Capt. Whitfield and Lieuts. Pratt, Tuttle and Adams, were taken by boat to New Orleans, and quartered on Rampart street. Here they remained till Sept. 20th. They were then transferred to Johnson’s Island, Lake Erie, where they arrived on Oct. 1, 1863. Lieut. Adams was exchanged in the spring of 1864, rejoining his company in May. Lieut. Pratt was paroled Sept. 16, 1864. Capt. Whitfield and Lieut. Tuttle remained at Johnson’s Island till the close of the war.

PRESENT OR ACCOUNTED FOR

Of the regiment 610 enlisted men reported at the Parole Camp, and about 100 were absent, sick or unaccounted for. Of the regimental officers Maj. Knox was the only one present, the others being at Johnson’s Island. There were about a dozen company officers present; each company, with the exception of K, having one or more representatives.

IN CAMP AT MERIDIAN

On Nov. 10th the regiment arrived at Meridian, Miss., having been assigned to Polk’s Corps, Army of the Mississippi, Gen. Joseph E. Johnston, commanding. Some of the non-commissioned officers of Co. K having requested to be restored to the ranks, the following reorganization was ordered: O. Sergt., Norman Cameron, 2d Sergt., Wm. H. Fay, 3d Sergt., C. Hardie Royals, 4th Sergt., M. D. Lamar, 5th Sergt., D. P. Smith, Corporals, E. L. Averhart, O. M. Blaylock, G. Hearn and J. D. Rice.

Lieut. Haley of Co. G was assigned to the command of Co. K, but was in a few weeks replaced by Lieut. Johnson, of Co. F.

The regiment was armed with new Austrian rifles, and the old routine of drill was once more resumed. Co. K made rapid progress and was complimented by Maj. Knox, by being excused from evening drill after Nov. 26th on account of its proficiency.

On Nov. 25th the regiment received two months’ pay to April 30th, and on Dec. 4th, was paid to Oct. 31st, with all arrearages, including $50 bounty and commutation for clothing; about $125,000 was disbursed to the regiment at this time. A limited amount of clothing was also issued, and some shoes, but the latter were scarce, only 15 pairs to the regiment. Rations were of good quality, and much more plentiful than ever afterwards, consisting of corn meal and a little flour, beef, bacon, sweet potatoes, salt, vinegar and soap. Early in November orders were issued to build log barracks for winter quarters, 18 by 22 feet each designed for 25 men.

The regiment had been declared exchanged on Oct. 16th, but it was soon known in camp that the Federals had denied the validity of the exchange, disputes having arisen in regard to the cartel. In camp the subject was discussed with much interest, especially the question what would be our fate if recaptured by the enemy. Political questions of the day now crept into our camp fire discussions, especially the acts of the Confederate Congress relative to the army. The act restricting furloughs and other privileges and offering in lieu thereof increased pay, also the act forcing men who had put in substitutes to report for duty were subjects of debate, and the former was bitterly denounced.

The post Company K First Alabama Regiment – THREE YEARS IN THE CONFEDERATE SERVICE CHAPTER VII appeared first on Digital Alabama.

]]>Siege and surrender of port Hudsonthe investment-SKIRMISHING-THE FIRST GRAND ASSAULT

ASSAILED AND ASSAILANTS-DOUBLY ARMED-LIEUT.

PRATT AT BATTERY II-THE ESSEX DRIVEN OFF-

LIEUT. ADAMS ELECTED-ARTILLERY PRACTICE-AS SAULT OF JUNE I4TH-EFFECT OF BUCK AND BALL-

BANKS INHUMANITY-LEAD FOR WATER-A GALLANT

CORPORAL-BATTERY I I SILENCED-GALLANT SCHUR-

MURS DEATH-THE SUNKEN BATTERY-MULE AND

PEAS-THE FALL OF VICKSBURG-UNCONDITIONAL

SURRENDER-GEN. GARDNERS SWORD-CASUALTIES

OF THE FIRST.

The post Company K First Alabama Regiment – THREE YEARS IN THE CONFEDERATE SERVICE CHAPTER VI appeared first on Digital Alabama.

]]>On the 21st, Gen. Gardner sent out Col. Miles, with 400 cavalry and a battery, to reconnoitre in the direction of Plains Stores. About four miles from Port Hudson they encountered Gen. Augur’s advance, and a severe skirmish of two and a half hours followed. The Confederate loss was thirty killed and forty wounded. At the same time Col. Powers cavalry, 300 strong, had a skirmish on the Bayou Sara road, and, being cut off, did not return to Port Hudson. When night fell the other forces were recalled within the fortifications. From Saturday, the 23d, to Tuesday, the 26th, the enemy were engaged in taking positions, the close investment being completed on the 24th. The First Alabama, with the exception of detachments at the guns, went to the front on the 23d, and were stationed on the northern line, at that time unfortified. Col. Steadman having been assigned to the command of the left wing of the garrison, Lieut.-Col. Locke commanded the regiment. Gen. Beale had command of the centre, and Col. Miles of the right. On the 24th there was heavy skirmishing, the First Alabama being engaged. The same day an order was issued for the brass rifle to be taken to a redan near the Jackson Road. Lieut. Frank, with a detachment of the sick and cooks the only men of the company in camp went with the gun and opened fire at long range upon a battery of the enemy, which was soon silenced. This gun remained at the Jackson road redan during the entire siege, the gunners suffering severely, and the gun being several times dismounted. On the 25th the First Alabama was again heavily engaged skirmishing, keeping back the enemy, while at the same time hurriedly fortifying, and lost twelve or fifteen men in killed and wounded. On the 26th the 30-pound Parrott was sent down to Battery No. 11 with a detachment of Co. K, under command of Lieut. Pratt, Sergt. Williamson, gunner, and a 24-pounder, rifled, was transferred from Battery No. 2 to No. 1. Lieut. Tuttle was in charge of Battery No. 1, and Lieut. Frank remained at the Jackson redan with the brass gun. Most of the 24-pounders were transferred from the river batteries to the fortifications, their places being supplied with Quaker guns. On the 26th there was but little firing, both armies preparing for the work of the following day.

Early on the morning of the 27th the enemy opened a heavy fire from both the land batteries and the fleet, and at 6, a. m., the Federal troops advanced to the assault. The heaviest attack was directed against the Confederate left, the assaulting column consisting of Grovers and Emory’s divisions, Weitzel’s brigade and the two regiments of negro troops. On the extreme left the negroes, supported by a brigade of whites, crossed Sandy Creek and assaulted the position held by Col. Shelby with the Twenty-ninth Mississippi. They advanced at a double-quick till within about 150 yards of the works, when the 24-pounder in Battery No. 1, manned by Co. K, and two pieces of light artillery on Col. Shelby’s line, opened on them; at the same time they were received with volleys of musketry from the Mississippians. The negroes turned and fled, without firing a shot. About 250 of them were killed and wounded in front of the works; but the Federal reports stated that 600 were killed and wounded. If this were correct, they must have been shot down by the white brigade in their rear; and, indeed, volleys of musketry were heard in the direction of their flight. The First Alabama, Lieut.-Col. Locke, and the Tenth Arkansas, Col, Witt, engaged the enemy outside the entrenchments in the thick woods, and fought most gallantly; but were compelled, by the heavy force brought against them, to fall back across Sandy Creek. Col. Johnson, with the Fifteenth Arkansas, 300 men, occupied and fortified a hill jutting out from the line, and held it till the close of the siege, though desperate efforts were made to dislodge them; on the 27th they repulsed a very heavy assault, the enemy’s dead in front of the position numbering eighty or ninety. Gen. Beale’s command in the centre, and Col. Miles on the right, were assailed by Augurs and Shermans divisions about 2, p. m., but the enemy was everywhere repulsed with heavy loss. At the Jackson Road the detachment of Co. K, Lieut. Frank commanding, who were serving the brass rifle, were, with but one exception, killed or wounded. While ramming a charge home, Private Henry Smith was mortally wounded by a sharp-shooter; Corp. Fergerson promptly stepped to his place, and was instantly fatally shot. In the meantime Private Hayes had been stricken down. Private Sears was busy attending the wounded and Lieut. Frank and Sergt. Ellis fired the gun themselves several rounds, the former pointing and the latter loading. While doing this Lieut. Frank fell, pierced by a Minieball; by his request, Sergt. Ellis carried him out of the battery to Gen. Beale’s headquarters, and gave him some water from the Generals canteen. Sergt. Ellis then asked for more men, and the General sent his courier to the rear for a detachment, which came under Lieut. Tuttle’s command. Lieut. Frank and Corp. Fergerson died that night; Private Smith lingered until July 10th; Private Hayes wound was slight. Near the camp, Private Winslett was instantly killed by a shell while on his way to Battery No. 11 with the Parrott gun. The final effort of the day was made about 3, p. M., when the enemy, under cover of a white flag, made a dash on a portion of our lines, but they were easily repulsed. All day the fleet kept up an incessant firing upon the lower batteries, but did no damage. The Confederates had about 5,500 muskets at the breastworks; and had the men been evenly distributed, they would have been about three feet apart. Fortunately, the nature of the ground enabled Gen. Gardner to leave long stretches of the works defended only by pickets; and, as the charges were not simultaneous, troops were hurried from one point to another where most needed. The fortifications, as previously stated, consisted of an ordinary field earthwork, over any portion of which, at the beginning of the siege it was materially strengthened during the 48 days at exposed points a fox hunter could have leaped. In some places, in fact, as in front of the First Alabama, there were no breastworks. Against this small force and weak defences Banks hurled nearly his whole army of 25,000 men, who fought bravely, but were badly handled. Gen. Banks loss was 293 killed and 1,549 wounded; the Confederate loss was about 200 killed and wounded. The Confederates picked up outside the works the following night a considerable number of Enfield rifles. These guns, with others subsequently captured, were retained at the works, and ere the close of the siege most of the men were armed with two guns each a musket loaded with buck and ball for use at close quarters, and a rifle for sharp shooting. As the fixed ammunition for the Enfields became exhausted, the men used the powder from musket cartridges, and for lead picked up Minieballs fired into the place by the enemy. These Yankee leaden missiles were also used instead of canister and were so thick on the surface of the ground within our lines, that it was but the work of a few minutes to pick up enough to charge a 12-pounder gun.

During the bombardment, on the 27th, a rifle shell from the fleet struck in Battery No. 5 disabling the 10-inch Columbiad carriage and killing a private of Co. G, First Alabama. A squad from Co. K worked in that battery on the nights of the 27th and 28th in dismounting and remounting, after the repair of the carriage, this 10-inch gun, which was ready for service again on the 29th. The man who was killed was standing on the carriage and was literally torn to pieces.

On the 28th there was a cessation of hostilities at the breastworks for the purpose of burying the dead. Gen. Banks did not deem it worth while to bury the colored troops who fought nobly, and their bodies lay festering in the sun till the close of the siege, when the colored regiments gathered the bones of their unfortunate brothers-in-arms and buried them.

At 7 p. M. the truce ended and the enemy made a furious rush upon the position held by the First Alabama. The fighting lasted nearly an hour, but the enemy were gallantly repulsed. The armistice did not embrace the river batteries and fleet, and the firing from the latter was unusually heavy. As previously mentioned Lieut. Pratt had received orders to take the 30-pounder Parrott, with a detachment from Co. K to Battery No. 11. An old 24-pounder, rifled, manned by a. detachment from Col. DeGournay’s battalion was also ordered to report to him at the same battery. His orders were to open upon the enemy’s fleet at daylight, but owing to the darkness of the night and the road being torn up by shells, it was after sunrise when the guns were got into position. The battery was very small, having been built for one gun only, and the parapet was but little over knee-high. About 6 A. m., everything being in readiness, Lieut. Pratt opened fire with the two guns upon the Essex anchored one mile or more distant. Within ten minutes the little battery was receiving the concentrated fire of the fleet including the six mortar-boats. The Essex, owing to her position, was the most accurate in her fire; three shells from her nine-inch guns exploded on the platform of the battery, and one struck a canteen hanging on the knob of the cascable of the Parrott. Private Joe Tunnell was slightly wounded by this shell; he was thrown upon his face and it was supposed he was killed, but he got up and brushing the dirt from his face exclaimed, Well, boys they liked to have got me. His wound though not serious disabled him, and Lieut. Pratt, in addition to his own duties as commander, had to assist in serving the gun. Lieut. Pratt was himself wounded during the action, but did not leave the battery; he was standing on the parapet watching the effect of the fire, when a shell exploded in the earth under his feet, and threw him into the battery, while fragments of the shell struck him on the hand and hip. Never did men act with more coolness than those at these guns, nor has artillery often been more ably served. There were fired from Co. Ks gun 49 shot and shell, and from the other piece 50. The enemy’s vessels were struck repeatedly; one shell from the Parrott was seen to enter a port-hole of the Essex, after which she closed her ports and, without firing another shot, retired out of range. The Genesee was also struck, and it was thought partially crippled. In addition to the casualties in Co. K, one man at the other gun was wounded.

The enemy made no more general assaults upon the works until June 14th, but in the meantime were approaching by parallels and planting batteries of heavy siege and naval guns. A steady fire was kept up day and night both by the fleet and the land batteries. There were about eighty siege pieces in these latter. An eight-inch howitzer so planted as to enfilade a portion of the southern line of defences, caused much amusement as well as annoyance to the Confederates. It was fired with light charges so as to make the shell ricochet and was, in consequence, christened Bounding Bet by the men, who speedily sought cover whenever they saw a puff of smoke from it. The deadly missile would go rolling and skipping along the inside of the line of works, finally exploding; one, that failed to burst, was opened and found to contain 480 copper balls of less than half an inch in diameter.

The sharp shooters were constantly engaged, and a man could scarcely show his head above the breastworks, at the more exposed points, without its being made a target. On May 31st the Parrott gun in Battery n fired a few rounds at the fleet. Soon after this Co. K was given a 24-pounder siege gun on the south side of the works named, by the company that had formerly used it, Virginia, and the Parrott was transferred to DeGournay’s battalion.

On the 3rd of June an election was held in Co. K to fill the vacancy caused by the death of Lieut. Frank. N. K. Adams received 37 votes, W. L. Ellis 7, scattering 4, and Lieut. Adams was duly commissioned. Hot weather had now set in, and this, coupled with constant exposure in the trenches, caused much sickness among the troops ; camp fever, diarrhoea, chills and fever soon reduced the number able to report for duty nearly one-third, and many of Co. K were among the sick. The company now served only at the artillery; Lieut. Pratt had charge of the Virginia, on the south side of the fortifications, Lieut. Tuttle had The Baby, brass rifle, at the Jackson Road, Lieut. Adams remained at Battery No. 1, occasionally relieving Lieuts. Pratt and Tuttle. Capt. Whitfield was placed in command of the Batteries 1, 2, 3 and 5, manned by detachments from Cos. K, A, G and B, respectively. The detachments of Co. K, at the Virginia and Baby, were daily relieved by the men held in reserve at Battery No. 1. The fire of the enemy’s land batteries was now very annoying, and the Confederate artillery could not fire a gun without having the fire of a dozen pieces concentrated upon it. Co. Ks brass gun was in this way several times silenced, and during the siege had two or three sets of wheels cut down. Finally the artillerists were compelled to withdraw their guns from the batteries and only run them in when a charge was made. In a measure to meet this emergency, the ten-inch Columbiad in Battery No. 4, on the river, was turned around and brought to bear by calculation on the batteries giving the most annoyance, and fire opened, apparently with considerable effect as the enemy’s fire slackened. Quite a number of eight and nine-inch guns were landed from the fleet, and placed in positions where they did much damage to the Confederate works. A battery of seven of these guns were located in front of Gen. Beale’s centre, one of six guns to the right of the Jackson Road, in front of Co. Ks brass gun, and one of seven guns in front of Col. Steadman’s command. From all of these a constant fire was kept up.

A singular phenomenon occurred on the night of June 13th; after a heavy cannonading an immense wave, at least six feet in height, rushed up the river, and at the same time Battery No. 6 caved into the river, one gun being lost. Whether the wave caused the bluff to cave in, or the bluff caving caused the wave, was a disputed question in camp, the general opinion, however, was that not a sufficient mass of earth fell to cause such a disturbance of the river.

About 3 a. m. on the 11th, after a heavy bombardment, the enemy made an attempt to storm the south-east angle of the works, but were repulsed. On the morning of the 13th a tremendous bombardment was opened, and a show of force was made. The firing then ceased and Gen. Banks sent in a flag of truce, demanding the surrender of the place. He complimented the garrison and commander in high terms; their courage, he said, amounted almost to heroism, but it was folly for them to attempt to hold the place any longer, as it was at his will, and he demanded the surrender in the name of humanity, to prevent the sacrifice of lives, as it would be impossible to save the garrison from being put to the sword when the works should be carried by assault; his artillery was equal to any in extent and efficiency, and his men out numbered the garrison five to one. Gen. Gardner simply replied that his duty required him to defend the post.

Before day on the morning of June 14th the enemy’s land batteries and the fleet opened fire with unusual rapidity, and about daylight the assault began. From the north-east angle to the Jackson Road the fighting was the most severe; the line between these points was defended by the First Mississippi and Forty-ninth Alabama and three or four pieces of artillery, including Co. Ks brass rifle at the Jackson Road. Gen. Banks plan of attack was as follows: two regiments of sharp shooters were ordered to advance as skirmishers, these were followed by a regiment with hand grenades, while another rolled up cotton bales to fill the ditch. Weitzel’s brigade and two brigades commanded by Cols. Kimball and Morgan, all under command of Gen. Weitzel, formed the storming party. On the left of this command was Gen. Emory’s division under command of Gen. Paine.

The Federals advanced, through their parallels, to within three hundred yards, and then, under cover of the dusk of the early morning and the smoke of their artillery, formed their line of battle, and advanced to the assault, in many places approaching to within ten feet of the works. They were received, however, with so deadly a fire of buck and ball that they were everywhere driven back with heavy loss, or crouched in the ditch for protection. By mere physical pressure of numbers some got within the works, in front of the First Mississippi and Forty-ninth Alabama regiments, but were instantly shot down. Co. Ks brass rifle did good execution; Lieut. Tuttle was in command and Sergt. Royals was gunner. In the midst of a terrific shower of rifle balls, it was served with coolness and deliberation. The enemy’s hand grenade experiment proved an unfortunate one for the assailants, as very few exploded when thrown int hey were percussion grenades but when thrown back by the Confederates, from the slightly elevated works, into the midst of the Federals below, they exploded, carrying death to their former owners. The fight lasted, with great severity, for about two hours, when the infantry fell back, but a heavy artillery fire was kept up all day. About one hundred prisoners were captured in the ditch near the Jackson Road, being unable to retreat. Among the Federal troops, who especially distinguished themselves here, were the Eighth New Hampshire and Thirty-eighth Massachusetts regiments. The fighting was very severe in front of the First Alabama, but the enemy did not get so near the works. On the right a feint was made, but the enemy did not approach to within close musketry range. In front of the 24-pounder, Virginia, manned by Co. K, they approached near enough for shrapnel, and Lieut. Pratt sent a few shell into their ranks, but they soon withdrew. The enemy’s official report of the losses, was 203 killed, 1,401 wounded, 201 missing, total 1,805. Probably many of those reported missing were killed, as there were 260 Federal dead buried in front of the centre alone, while the number of prisoners taken was but about 100.

After this repulse, Gen. Banks sent no flag of truce for the purpose of burying the dead or removing the wounded for three days. On the 17th Gen. Gardner sent out a flag and requested the Federal commander to bury his dead; but he replied that there were no dead to bury. Gen. Beale, at Gen. Gardner’s request, then sent a flag to Gen. Augur, who commanded in his front, calling his attention to the unburied dead. Gen. Augur replied that he did not think there were any there, but would grant a cessation of hostilities to see. Parties of Confederates were detailed to collect and pass over to the Federals the dead near our lines, and, as above stated, 260 were thus removed. Among the dead was found a wounded officer a Captain who had been lying exposed to the sun for three days without water, and was fly blown from head to foot. At the close of the siege the writer was informed that this man recovered. During the three days many wounded must have perished on the field, as they could be heard crying piteously for help. A Confederate, more tender-hearted than Banks, was shot by the enemy while carrying a canteen of water to a wounded Federal who lay near the works. In front of Col. Steadman’s position the dead were not buried, and their bodies could seen from the breastworks, at the time of the surrender, twenty-five days after the fight.

On June 15th Co. K removed a 42-pounder, smooth bore, barbette carriage, from Battery 2 or 3 to Battery No. 1, to replace the 24-pounder siege piece which had been sent to the land defences.

During the remainder of the month, there was an incessant fire of sharp shooters and artillery. To the left of the Jackson Road, the enemy built up a tower of casks filled with earth, two or three tiers in height, from which their sharpshooters were able to over look the Confederate works, and keep up an annoying fire. It was not more than 60 yards from our lines, but the two or three pieces of artillery which could be brought to bear on it, were commanded by a score of the enemy’s heavy guns, and could not be used to batter it down. At other portions of the line the enemy rolled bales of cotton to within close range, and surmounted them with sand-bags, arranged with narrow loop-holes, for the sharpshooters. On the 25th, Corp. L. H. Skelton, of Co. F, First Mississippi regiment, crawled out and placed port-fires in the bales of cotton and fired them; the first attempt failing, he went out a second time and succeeded in burning a number of bales. On the night of the 26th, 30 men made a sortie near the south-east angle, spiked the guns of one of the enemy’s batteries, and captured seven prisoners.

Co. K began about the last of June to make an excavation, partially behind the Jackson Road redoubt, in which to place their brass rifle, with a view of battering down the sharp shooters tower. It was intended to be so constructed as to be protected from the enemy’s artillery, but as the work could only be done at night, it was not completed in time to be of essential service. J. McCarty was killed at the brass gun, on June 23rd, by a fragment of a shell. This was the last casualty in the company during the siege. While these events were in progress in the centre, the enemy had been busy, on the extreme right, preparing to assault Battery No. n, which was the key to the Confederate works. They erected a battery containing 17 eight and nine-inch smooth bore guns and 20-pounder Parrotts, on the opposite side of the ravine and distant only 150 yards. On the opposite bank of the river, Parrott guns, manned by United States Regulars, were planted. Lieut. Schurmer, of DeGournay’s battalion, was in command of Battery 11, and its defense could have been entrusted to no more gallant gentleman. Gen. D. H. Hill, in a letter to the writer, said, I knew Schurmer well at Yorktown, and in a subsequent number of his magazine related the following incident connected with the siege of that place, where Schurmer was under his command : Schurmer was in charge of a 42-pounder, and especially distinguished himself by the accuracy of his fire. It was regarded as remarkable, even in the Federal army, and one of the French princes, on McClellan’s staff, made mention of it in a report of the operations at Yorktown. When Yorktown was evacuated he remained in Fort Magruder firing the 42-pounder all night, thus contributing essentially to the deception of the enemy. He attempted to escape the next morning on foot, but, exhausted, fell asleep by the wayside and was captured.

In Battery No. 11 was the 30-pounder Parrott formerly in Battery No. 1. On Friday morning, June 26th, the fleet and land batteries opened a terrific fire on the earth work, and in a few minutes Co. Ks old gun was forever silenced. One shell exploded in the muzzle, breaking off about a foot of it, while the carriage was struck by five or six shots and cut down. Three times during the day the Confederate flag was shot away, falling outside the works, and each time Schurmer, regardless of the storm of shot and shell, replaced it. Without intermission by day or night, the enemy kept up this fire until the 30th, and under cover of it advanced their parallels down through the ravine to within fifteen feet of the battery. Gallant Schurmer never relaxed his heroic devotion to duty, and on the 29th fell dead at his post. The next day while the Confederates were rolling ten-inch shells over the parapet into the enemy’s ditches, a storming party of some two hundred men made a rush for the battery. Its squad of defenders were hastily reinforced and the assailants were driven out, leaving sixteen dead inside our lines. On July 4th the Federal sappers were driven out of their ditches by hand grenades, but they claimed, after the surrender, that they had mined Battery 11 and had 3,000 pounds of powder under it ready to explode had the siege been further prolonged. The enemy’s batteries, on the west bank of the river, occasionally opened but were always silenced by Batteries 3, 4 and 5. On the centre of the south side the enemy kept quiet, and the detachment of Co. K, at the 24-pounder, had but little to do. A few shots were fired on the 2nd of July.

At the north-east angle the enemy, during the latter part of June and the first of July, were very busy mining, but the Confederates were no less industrious. An inner line of works extending across the angle was thrown up, the enemy’s mine was countermined, and on the 4th blown up. The enemy’s sappers were also constantly annoyed by rolling ten-inch shells into their ditches. On July 4th the enemy fired salutes from all their batteries with shotted guns, making it a warm day within our lines.

On the night of the 6th Co. K completed the sunken redoubt for the brass rifle, and on the following morning opened fire on the sharpshooters castle; but the embrasure was incorrectly laid off, and the gun could not be brought to bear on the tower without firing so close to the side of the embrasure as to cause the earth to cave in; so that, after firing three shots, the gun could no longer be brought to bear on the mark. Owing to the fire of the sharpshooters, nothing could be done to correct the mistake till night. The necessary changes in the earthwork were made that night, and on the morning of the 8th the detachment was at the gun ready to open fire, when the flag of truce was raised.

The condition of the garrison was now such as to limit further resistance to a few days. Early in June the enemy’s shells had fired the commissary building and mill, destroying several thousand bushels of grain and the chief means of grinding what was left. Fortunately, the only locomotive of the Clinton and Port Hudson Railroad was at Port Hudson. This was blocked up, and furnished power to drive a portable mill. The corn, with the exception of two or three days rations, held in reserve for an emergency, failed the last of June, and the supply of meat failed about the same time. There still remained a considerable stock of field peas and mules. When the men of the First Alabama were asked if they would eat mule, they replied, Yes; give us dog if necessary. The same spirit animated the whole garrison. Mules were slaughtered, and the meat issued on the 29th or 30th of June; the peas were issued whole and also ground into meal. Those sick in camp and hospital were fed by their comrades upon rats, daintly served up as squirrels. In the pea diet there were some drawbacks ; the peas were stored in bulk on the floor of the church, and the concussion of the bombardment had broken in every pane of glass in the building. This, in comminuted form, was mingled with the peas; and it was no unusual incident to be made painfully aware of its presence in masticating the peas. There were some among the garrison who could not stomach the mule, and, to satisfy these, an unexpected discovery was made of sixty barrels of corn beef. Some wonder was expressed as to this windfall, but it was accepted, eaten in good faith and pronounced excellent. It was not until after the surrender that those who ate it knew that it was carefully corned mule.

The ammunition, although it had been economized, was so nearly fired away that another general assault would have exhausted the supply. Nearly every cannon on the land fortifications had been disabled, and in the river batteries there remained but nine or ten fit for use.

On the first day of the siege there were 5,500 men at the breastworks; some 600 had been killed and wounded; many had died of disease, and at least 2,000 were suffering from camp-fever and diarrhoea, many of them being unable, under any emergency, to fire a musket.

This was the situation when, on the 7th of July, salutes from the enemy’s batteries and fleet, and continued cheering all along their lines, announced some great event. The lines were so close that the garrison was not long kept in ignorance that Vicksburg had fallen. That night Gen. Gardner summoned a council of war, consisting of Gen. Beale, Cols. Steadman, Miles, Lyle and Shelby, and Lieut.-Col. Marshal J. Smith. They decided unanimously that it was impossible to hold out longer, inasmuch as the provisions were nearly exhausted; of ammunition there remained but twenty rounds per man, with a small supply for the artillery; and a large proportion of the garrison were sick or, from exhaustion, unfit for duty. A communication was at once sent to Gen. Banks, stating what had been heard in regard to the fall of Vicksburg, asking for official information and notifying him that, if the report was true, Gen. Gardner was ready to negotiate for terms of surrender. Gen. Banks reply, enclosing a despatch from Gen. Grant, announcing the fall of Vicksburg, was received before day. Gen. Gardner at once appointed Cols. Miles and Steadman and Lieut.-Col. Smith commissioners to arrange terms of surrender. To represent the Federals, Gen. Banks appointed Brig.-Gen. Chas. P. Stone, Brig.-Gen. Wm. Dwight and Col. Henry M. Birge. The following terms were drawn up and signed:

Article 1 Maj.-Gen. Frank Gardner surrenders to the United States forces, under Maj.-Gen. Banks, the place of Port Hudson and its dependencies, with its garrison, armaments, munitions, public funds and materials of war, in the condition, as nearly as may be, in which they were at the hour of the cessation of hostilities, namely, 6 o’clock, A. M., July 8, 1863.

Article II The surrender stipulated in Article I is qualified by no condition save that the officers and enlisted men comprising the garrison shall receive the treatment due to prisoners of war according to the usages of civilized warfare.

Article III All private property of officers and en listed men shall be respected, and left to the respective owners.

Article IV The position of Port Hudson shall be occupied tomorrow at y o’clock, a. m., by the forces of the United States, and its garrison received as prisoners of war by such general officers of the United States service as may be designated by Gen. Banks with the ordinary formalities of rendition. The Confederate troops will be drawn up in line, officers in their positions, the right of the line resting on the edges of the prairie south of the railroad depot, the left extending in the direction of the village of Port Hudson. The arms and colors will be conveniently piled, and will be received by the officers of the United States.

Article V The sick and wounded of the garrison will be cared for by the authorities of the United States, assisted, if desired by either party, by the medical officers of the garrison.

Chas. P. Stone, Brig-Gen. U. S. A.

W. N. Miles, Col. Com. Right Wing, C. S. A.

Wm. Dwight, Brig.-Gen., U. S . A.

I. G. W. Steadman, Col. Com. Left Wing, C. S. A.

Marshal J. Smith, Lt.-Col. & Chief of Art., C. S. A.

Henry W. Birge,

Col. Com. 5th Brig., Grover s Div., U. S. A.

Approved,

N. P. Banks, Maj.-Gen.

Approved,

Frank Gardner, Maj.-Gen.

So

On the morning of the 9th, the garrison was formed in line and two officers were sent, by Gen. Gardner, to conduct in the Federal officer deputed to receive the surrender. This was Gen. Andrews, who entered the lines on the Clinton Road shortly after 7 o’clock. Gen. Gardner met him at the right of the line and delivered up his sword, saying, General, I will now formally surrender my command to you, and for that purpose will give the command Ground arms. Gen. Andrews replied, that he received Gen. Gardner’s sword, but returned it to him for having maintained his defence so gallantly. Meanwhile the Federal infantry moved in, and the wings resting on the river cut off any attempt to escape. A few officers and men, including Maj. Knox, of the First Alabama, concealed themselves near the outer lines, prior to the surrender, and the following night made their escape. There were, all told, 6,233 prisoners surrendered, but this included many non-effectives, such as teamsters, commissary, quartermaster and ordnance employees. At no time were there more than 5,500 muskets at the works. There were also surrendered 5,000 stand of firearms and 51 pieces of artillery, the latter including a number of small cast-iron guns, not mounted, and a number of disabled guns. The small number of muskets surrendered is accounted for by the fact that many of the soldiers threw their guns into the river or broke them.

The casualties in the First Alabama regiment during the siege were as follows :

FIRST ALABAMA REGIMENT. 81

Co. A, Killed, 3, Wounded, 17, Died of disease, 4

Co. Ks casualties were as follows : Lieut. Frank, Corp. Fergerson and Private Winslett killed May 27th; Private McCarty, killed June 23 ; Private Henry Smith, mortally wounded, May 27th, died July 10th; Lieut. Pratt and Private Josiah Tunnell, wounded May 28th; Private Clark, wounded May 10th, at Troths Landing; Private Hayes, wounded May 27th and Sergt. Williamson, wounded during the siege. Private Boon, died June 29th, of disease, Private Scott, July 3d, Private Mills, July 5th, Private Holston, July 6th.

During the siege two or three private families remained in the town, but suffered no casualties excepting one accidental; a boy having found an unexploded shell was playing with it when it burst, seriously wounding himself and mother.

The post Company K First Alabama Regiment – THREE YEARS IN THE CONFEDERATE SERVICE CHAPTER VI appeared first on Digital Alabama.

]]>The post THREE YEARS IN THE CONFEDERATE SERVICE: Chapter V appeared first on Digital Alabama.

]]>Col. Steadman at once began a strict system of discipline and drill. The following was the order of the day: Reveille at daybreak with roll-call, inspection of arms and policing of camps; 6 a. m., drill in the school of the soldier; 7 A. M., breakfast; 8.30 a. m., guard mounting; 9 A. m., non-commissioned officers’ drill; 10 a. m., drill in the school of the company; 12 m., dinner; 1 p. m., skirmish drill; 3 p. m., battalion drill; 5 p. m., dress parade; sunset, retreat; 9 P.M., taps. Companies assigned to batteries drilled at the guns at the hours for the company drill. Strict regimental guard was kept up, all the requirements of the army regulations being enforced.

The first call to action was on Sunday, November 16th, 1862, when the Federal fleet appeared at the head of Prophet’s Island, below Port Hudson. The regiment was ordered to strike tents and pack knapsacks; while the left wing, including Co. K, was deployed along the bank as sharp-shooters. In a short time the fleet retired and the troops were ordered back to camp.

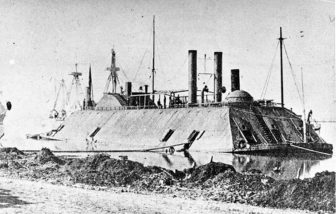

Essex was formally transferred to the Navy in October 1862 and remained active on the rivers through the rest of the Civil War. She bombarded Port Hudson, Louisiana, and helped with the occupation of Baton Rouge in December 1862. In May-July 1863 she participated in the capture of Port Hudson. She took part in the Red River expedition in March-May 1864. Essex was decommissioned in July 1865. After her sale to private interests in November of that year, she reverted to the name New Era . She was scrapped in 1870.

On the evening of December 13, 1862, Capt. Boone’s company of Light Artillery, supported by Co’s D and F of the First Alabama, crossed the river and after dark moved down opposite the anchorage of the iron clad Essex and a wooden vessel. The guns, consisting of two smooth-bore 6-pounders and one 12-pound howitzer were planted behind the levee, and at daylight the next morning fire was opened on the wooden vessel. The fire was so effective that the Essex had to steam up and interpose her iron sides for the protection of her consort. Both vessels then retired down the river. Although the Federal vessels kept up a heavy fire our loss was but one man wounded.

During the early part of December the regiment was busy constructing barracks of willow logs, the roofs covered with cypress boards. Co. K built two cabins, which were completed about the last of the month. They were 18 by 22 feet, with a large fireplace at each end. The chimneys were built of sticks daubed with clay. An open door way furnished entrance and light, while ventilation was secured by leaving the upper cracks between the logs un-chinked; bunks were built in tiers along the walls, and the men were very comfortably quartered for the winter.

A PARROTT FOR CO. K

On December 31st Capt. Whitfield received the promise of a one gun battery—a 30-pound Parrott gun— on the condition that his company build the battery and magazine. The battery was laid off above the redan, then known as Battery No. I, but separated from it by a deep ravine. Co. K worked alone on their battery till January 8th, when details were made from the infantry companies of the regiment to assist them. By the 18th of January the work was so nearly completed that the gun was brought up from Battery No. 11 and put into position. The magazine was not completed till the last of February, the powder being stored in it on March 2, 1863. The gun was christened the “ Lady Whitfield.”

On December 26th, Lieut. Tuttle and Corp. John Hearn left for Alabama to secure recruits for Co. K. They returned in February having secured 45, as follows:—

Adams, Jesse, Alexander, J. L., Boggan, Jno., Boggan, T. M., Boone,- Byrd, J. H., Callens, R. H., Clark,- Deno, M., Douglass, Wm., Dubose, Wm., Durden, G. W., Glenn, Simeon, Golsan, P. G., Gorman, John, Haley,- Hamilton, John, Hern, M., Hays, J., Jenkins, E., . Kirkpatrick, V., Lamar, M. D., Leysath, E., Lewis, J., Mobile Co.

Autauga Co. Wilcox Co. Autauga Co. Butler Co. Mobile Co. Pike Co. Autauga Co.

Mobile Co.

Pike Co.

Butler Co. Autauga Co. Butler Co. Montgomery Co.

Martin, G. F.,Merritt,-Mills,McCarty, J., . McDonald,- Autauga Co.

Owens, J.,Autauga Co.

Scott, B. L., .Scott, C, H.,Shaver, J. H., Conecuh Co.

Simpson, J. L., Butler Co.

Shoals, J., Schein, J., Montgomery Co.

Smyth, A. C. Smith, Henry, Butler Co.

Stuart, J. J., Wilcox Co.

Tarleton, M.,Tharp, J. P.,Vaughn, Wm, Lowndes Co.

White, A. J., Wilson, T. A., Winslett,- . Autauga Co.

In addition to these Henry Fralick, of Autauga Co., joined the company in September, 1862.

Second Lieut. Dixon S. Hall having resigned from ill health, Junior Second Lieut. Tuttle was promoted, and an election was held March 4, 1863, for Junior Second Lieutenant, resulting as follows: John Frank, Jr., 35; Norman Cameron, 20; N. K. Adams, 8 ; John Frank, Jr., was thereupon duly commissioned.

On March 12, 1863, Moses Tarleton, of Lowndes Co., one of the recruits, died, and was buried with military honors. This was the only one of the company, owing in other cases of death to lack of opportunity, to whom these honors were paid.

WHITFIELD’S LEGION

Company K, having a full complement of men, and having but one gun in its battery, was divided as to duty. One portion was drilled as heavy artillery, another portion as infantry, while Lieut. Tuttle with the remainder was detailed to act with a detachment of the regiment under command of Major Knox as river police. The company was jocularly known, in consequence of this division, as “ Whitfield’s Legion.”

On the afternoon of March 13, 1863, several of Admiral Farragut’s vessels appeared in sight below Port Hudson, anchoring near the head of Prophets Island, and when the fog lifted on the morning of the 14th, his whole fleet lay at anchor just out of range of our guns. There were eight magnificent war steamers, one iron clad and six mortar boats.

The Union Army, ably supported by the Mississippi Squadron, was pressing, on Vicksburg from above, and Farragut wanted to assist in the campaign by blockading the mouth of the Red River from which supplies were pouring eastward to the Confederate Army. Meanwhile, the South had been fortifying its defenses along the river and had erected powerful batteries at Port Hudson, Louisiana. On the night of 14 March 1863, Farragut in Hartford and accompanied by six other ships, attempted to run by these batteries. However, they encountered such heavy and accurate fire that only the flagship and Albatross, lashed alongside, succeeded in running the gauntlet. Thereafter, Hartford and her consort patrolled between Port Hudson and Vicksburg denying the Confederacy desperately needed supplies from the West.

The flag ship was the steam-frigate “ Hartford,” with an armament of 26 eight and nine-inch Paixhan guns. The “ Richmond,” a ship of the same class, was armed with 26 eight and nine-inch Columbiads ; the side-wheel steam-frigate “ Mississippi ” had 19 eight- inch guns, 1 ten-inch, 1 twenty-pound Parrott and 2 howitzers in her tops; the Monongahela, steam-sloop of war, carried 16 heavy guns; the gun-boats “ Kineo,” “Albatross,” “Sachem,” and “Genesee” each carried 3 heavy Columbiads and 2 six-inch rifles. All of these but the “ Mississippi ” were screw propellers. In addition to the above vessels all of which, except the “ Sachem,” were to attempt to run the batteries, there was the iron clad “Essex” carrying 10 heavy guns and also six mortar boats, each carrying 1 thirteen-inch mortar. These last were to cover the advance of the fleet by fiercely shelling the Confederate batteries. The mortar-boats were moored close under the river bank at the head of Prophets Island, and were protected from the Confederate batteries by the bluff which at that point curved almost at a right angle. The “ Essex ” was anchored in the stream opposite the mortar-boats, and the other vessels some distance lower down but in sight.

On the afternoon of the 14th, the fleet opened fire apparently to get the range of our batteries. About seventy – five shot and shell were thrown, but the batteries made no response. All the batteries were manned as night approached, while the infantry were at the fortifications on the land side, prepared to resist any attack by Gen. Banks’ forces. Until 9.30 p. m. all was quiet, then a red light was displayed from the mast-head of the “ Hartford,” the signal for the fleet to prepare for action. As the vessels passed his station, about 11 p. m., Capt. Youngblood, of the Confederate signal corps, sent up a rocket and the sentinels on the batteries fired their muskets, conveying the alarm from the lower to the upper works. In a few minutes the eighteen guns in position along the bluff were ready for action. At the wharf lay two Red River transports unloading; on board all was confusion, the shrieks of the women, the shouts of the officers to their crews, the glare of light from the cabins and furnaces, contrasted strangely with the death-like stillness and darkness of the batteries on the bluff. Just as the transports steamed away from the wharf on their way to Thompson’s Creek, up which they sought safety, Gen. Gardner came dashing up to Battery No. 1, and seeing the lights on these vessels and mistaking them for the gun-boats called out to Capt. Whitfield, “

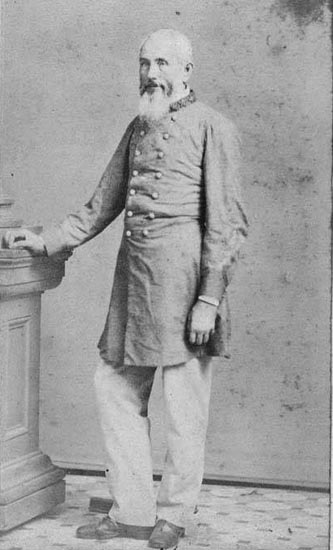

Franklin Kitchell Gardner (January 29, 1823 – April 29, 1873) was a Confederate major general in the American Civil War, noted for his service at the Siege of Port Hudson on the Mississippi River. Gardner built extensive fortifications at this important garrison, 16,000 strong at its peak. At the mercy of conflicting orders, he found himself besieged and greatly outnumbered. His achievement at holding out for 47 days and inflicting severe losses on the enemy before surrendering has been praised by military historians.

Why don’t you fire on those boats?” John Hearn, not recognizing the General, replied, “ They are our transports, you infernal thief.” The commandant, either not hearing or concluding that under some circumstances deafness was commendable, made no response.

So soon as the alarm was given, the Federal fleet began firing; the mortar-boats—the “ Essex ” and the “ Sachem ” — moored to the bank or lying at anchor, with guns trained during the preceding day, had quite accurate range; but the practice of the moving vessels was somewhat wild till they were at close quarters. Orders had been issued to permit the enemy to get well in range before opening fire, and it was not until the leading vessel was nearly opposite Battery No. 11 that the first gun was discharged from the bluff. Instantly flash after flash revealed the positions of the Confederate artillery. The “ Hartford,” with the “Albatross” lashed to her larboard side, was in the advance; the “Richmond” and “Genesee,” the “ Monongahela ” and “ Kineo ” followed, and the “ Mississippi ” brought up the rear.

At Battery No. 1 the upward passage of the fleet could only be traced by the flashes of its guns. Huge bonfires had been built under the bluff to illuminate the river, but the smoke of the pine wood only served to render impenetrable the darkness of the night, and they were immediately extinguished. Later in the battle, the signal corps, on the other side of the river, fired an old building, and the flames from this in a measure revealed the position of the vessels as they passed between it and the batteries. So soon as the Confederates opened, the fire of the fleet, no longer directed at random, was redoubled, and the roar of its hundred heavy guns and mortars, added to that of the rapidly-served artillery of the garrison, was fearful. Howitzers in the tops of the steamers swept the bluffs and gave some annoyance to the gunners. Leaving the rest of the ships to follow as best they could, the “ Hartford” and her consort moved steadily on past the fortifications, rounded the point, and, pouring a farewell broadside of grape and shrapnel into Batteries Nos. 1, 2, and 3, steamed out of range up the river.

The “ Richmond ” and “ Genesee ” followed close in the wake of the “ Hartford” till opposite Batteries Nos. 4 and 5, when a rifle-shell piercing the steam-drum of the former disabled her, and another shot passing through the smokestack mortally wounded Lieut. Boyd Cummings, her commander. A dozen other wounds in hull and rigging attested the accurate gunnery of the Confederates. Turning, by aid of her consort, both steamers came close under the bluff, where, for a few minutes, they were protected, and some one on board yelled out, with an oath, “ Now let us see you hit us ! ” A moment later, as they ran out into the channel, both were raked. A shell exploding in the ward-room of the “ Genesee ” set the vessel on fire, but the flames were speedily extinguished, and after running the gauntlet a second time, the crippled ships got back to their anchorage.

As Army forces ashore conducted a mortar bombardment, the squadron got underway about 22:00, heavier ships USS Hartford, USS Richmond, and Monongahela screening the smaller USS Albatross, USS Genesee, and USS Kineo from the forts, with steam frigate USS Mississippi bringing up the rear. In the course of the ensuing furious engagement, only Hartford and Albatross succeeded in passing upriver, Richmond losing her steam power early in the battle and drifting downstream out of range with Genesee lashed alongside. Monongahela grounded under the guns of a heavy battery, taking a pounding and losing six men killed and 21 wounded, including the captain, until she worked loose with Kineo’s aid. While attempting to continue upriver, her overloaded engine broke down, and the sloop was forced to drift downstream with Kineo. Mississippi—grounding at high speed—was hit repeatedly and set afire, eventually blowing up and ending the engagement.

The “ Monongahela”*and “ Kineo” met with but little better fortune. A 32-pound cannon-ball cut the tiller- ropes of the former, another shot demolished the bridge and seriously wounded Capt. McKinistry, her commander, while her decks were strewed with dead and wounded. About the time the tiller-ropes of the “ Monongahela” were shot away, a 32-pound ball struck the rudder-post of the “ Kineo.” Both thus disabled, the “ Monongahela” ran into the bank, and the hawsers which lashed the ships together parting, the “ Kineo ” shot ahead and also ran into the bank. Backing off, the “Kineo” dragged with her the “Monongahela”; but the propeller fouled in the parted hawser, and the two vessels drifted helplessly down the river, letting go their anchors when out of range.

BURNING OF THE “MISSISSIPPI”

Ordered upriver for the operations against Port Hudson, Louisiana, Mississippi sailed with six other ships lashed in pairs, while she sailed alone. On 14 March 1863, she grounded while attempting to pass the forts guarding Port Hudson. Under enemy fire, every effort was made to refloat her by Captain Melancton Smith and his executive officer George Dewey (later to achieve fame as an admiral). At last, her machinery was destroyed, her battery spiked, and she was fired to prevent Confederate capture. When the flames reached her magazines, she blew up and sank. Three of Mississippi’s men, Seaman Andrew Brinn, Boatswain’s Mate Peter Howard, and U.S. Marine Corps Sergeant Pinkerton R. Vaughn, were awarded the Medal of Honor for their actions during the abandonment. She lost 64 men, with the accompanying ships saving 223 of her crew.

The pilot of the steamship “ Mississippi,” confused by the smoke of the battle, ran that vessel ashore at the point directly opposite Batteries Nos. 3, 4 and 5. Her commander, Capt. Melancthon Smith, used every endeavor to get his vessel off, but in vain. In the meantime her guns poured forth an almost continuous sheet of flame. Deserted by all her consorts she received the concentrated fire of the batteries. A rifle shot, probably from Battery No. 1, knocked a howitzer from her maintop clear of the vessel into the water. One after another her heavy guns had been disabled, and thirty of her crew had fallen, when her commander gave the order to abandon her. The dead were left on the decks, four of the wounded were taken ashore, others leaped into the river; those who were unhurt got to shore some by swimming and others in the boats. Before all had left the doomed vessel flames burst forth, by whom set is a disputed question. Capt. Smith’ reported that he fired the vessel, while the men in the hot-shot battery as strenuously insisted that she was fired by them, another report stated that a shell exploded in some combustibles arranged on her deck for the purpose of firing her. Some of those who escaped to shore made their way down the river bank to the fleet, swimming the crevasses ; 62, including two officers, were taken prisoners the next morning. The flames spread rapidly, soon enveloping the hull and shrouds. As the flames reached the larboard guns, they were discharged one after another towards the vessels which had gone up the river, while shells on her decks kept up a constant fusilade. From the time that efforts had been given up to get her off, there had been a constant shriek of escaping steam from her safety valve. Lightened by the flames she floated off the bar and drifted, a huge pyramid of fire, down the river illuminating its broad expanse till all was bright as day, and revealing the shattered vessels of the fleet as they hastily steamed out of the way of their dangerous consort. Long after she had passed around the bend the light of the flames reflected on the sky marked her progress. About 5 a. m., when at almost the identical spot where the Confederate ram “ Arkansas ” was blown up, the fire reached the magazine and the “ Mississippi ” existed only in story. The shock of the explosion was felt at Port Hudson, twenty miles distant.

COMPARATIVE LOSSES

The battle lasted from about 11 p. m. to 2 A. m. Co. K fired their one gun 32 times. Lieut. Pratt had immediate charge of the gun, Capt. Whitfield being also present. Sergeants Ellis and Royals were the gunners and Wm. H. Fay the ordnance sergeant. Lieut. Tuttle was on duty with the river patrol. The eighteen Confederate guns fired altogether about six hundred shot and shell. Of which, according to Federal reports, at least one hundred struck the attacking vessels, as the “ Hartford ” alone was struck over thirty times. The loss of the First Alabama was three men slightly wounded. One man was killed at the land fortifications, and one man wounded in one of the lower batteries. Not a gun was injured.

The enemy’s losses may be summed up as follows: the “ Mississippi,” burned; the “ Richmond,” completely disabled and obliged to return to New Orleans for repairs; the “Genesee,” slightly damaged by fire; the “ Monongahela,” bridge shot away and tiller ropes cut; the “ Kineo,” rudder disabled and rigging badly cut up. Casualties, “ Hartford,” 3 killed and 2 wounded; “ Albatross,” 3 killed and 2 wounded; “ Richmond,” 4 killed and 7 wounded; “ Monongahela,” 7 killed and 21 wound¬ ed ; “ Mississippi,” 22 killed and 8 wounded; and 62 prisoners : total 39 killed, 40 wounded and 62 prisoners, including 2 commissioned officers. One of the latter, Midshipman Francis, was paroled in consideration of his gallant efforts to save the lives of some Confederate prisoners, who fell overboard from the flag of truce steamer “ Frolic,” at Baton Rouge, a few weeks before, while en route to be exchanged. The other prisoners were sent to Richmond. Federal accounts of the battle state that the fire of the batteries was so accurate as to threaten the destruction of every vessel exposed. The gunners of Battery No. 1 labored under a disadvantage, as the smoke settled in a dense bank in front of the battery, but there was reason to believe that their gun did good execution.

THE LAND ATTACK

At the outbreak of the Civil War, President Lincoln appointed Banks as one of the first ‘political’ major generals, over the heads of West Point regulars, who initially resented him, but came to acknowledge his influence on the administration of the war. After suffering a series of inglorious setbacks in the Shenandoah River Valley at the hands of Stonewall Jackson, Banks replaced Benjamin Butler at New Orleans as commander of the Department of the Gulf, charged with administration of Louisiana and gaining control of the Mississippi River. But he failed to reinforce Grant at Vicksburg, and badly handled the Siege of Port Hudson, taking its surrender only after Vicksburg had fallen.

Gen. Banks with 25,000 men was to have attacked by land, while Farragut assailed the river defences. On the evening of the 13th the divisions of Gens. Grover and Emory left Baton Rouge and were followed the next morning by Gen. Augur’s division. Gen. Banks establishing his headquarters at the crossing of the Springfield road, seven miles below Port Hudson. Friday afternoon the enemy’s advance guard encountered the Confederate pickets and a sharp skirmish followed, in which several men were killed and wounded. The following day there was another skirmish in which the Federals were worsted, losing a number of officers, killed, wounded and prisoners. They made no further demonstration till Monday when Gen. Rust’s brigade attacked their rear guard as they were retiring and drove them six miles. The main body made no offer of battle, and the rear guard burned the bridges to prevent further pursuit. Thus ingloriously ended this attempt to capture Port Hudson by a force many times that of the garrison.

The mortar fleet, “Essex,” and one or two other vessels, remained until March 28th, shelling the batteries, camps and transports at the wharves nearly every day, without, however, coming within range of the Confederate guns. On the 18th, the enemy landed a force of infantry and artillery on the west bank and burned the residence of Capt. Hines, the lower batteries shelling the raiders that night.

The “ Hartford ” and “ Albatross ” having gone up to Grand Gulf leaving the Red River open, several transports with supplies came down. On the 21st, while these were unloading, just above Battery No. 1,the fleet opened fire forcing them to steam up Thompson’s Creek. The rifle shells fell around our battery and camp. On the 24th, the enemy fired a sugar mill opposite Port Hudson our batteries shelling them as they retired. A battery of light artillery planted by the enemy behind the levee shelled our lower batteries on the 25th but without effect. On the 28th the fleet steamed down the river. Admiral Farragut with the “ Hartford,” “Albatross ”

A 413-ton side-wheel towboat, she was built at Cincinnati, Ohio, in 1854 and converted to a ram in March–May 1862 for Colonel Charles Ellet, Jr.’s U.S. Ram Fleet. She played a distant role in the 6 June 1862 naval action off Memphis, Tennessee, and subsequently took part in operations in the Yazoo River and against Vicksburg, Mississippi. On 25 March 1863, while commanded by Colonel Charles Rivers Ellet, Switzerland joined the ram Lancaster in an attempt to pass the Vicksburg fortress. Both ships were heavily hit by Confederate gunfire, with Lancaster being sunk. Despite her damage, Switzerland survived the trip and made a subsequent successful passage of the fortifications at Grand Gulf, Mississippi, on 31 March. She took part in operations on the Red and Atchafalaya rivers in May and June 1863. Later in the war, Switzerland was part of the Mississippi Marine Brigade.

and ram “Switzerland,” the last named having run the Vicksburg batteries, appeared above Port Hudson on April 6th, and on the 7th several vessels came up from below and exercised their guns for a while. There was a false alarm on the night of April 9th, caused by a raft with a fire on it floating down the river; it was boarded by the river patrol and the fire extinguished.

Rev. Mr. Baldwin, who had been appointed Chaplain of the regiment, preached his first sermon on Sunday, April 12th. Nothing of special interest beyond an occasional visit from the gun-boats occurred until May 5th, when the fleet above Port Hudson fired the “ Hermitage ” and another building. On May 6th Co. K received another gun, a rifled brass piece, 4 inches calibre, captured on Amite river. It was clumsily mounted on a 24-pounder siege carriage, and christened “ The Baby.” In anticipation of receiving this gun a battery had already been prepared for it beside the old one.

A SABBATH MORNING AT TROTH’S LANDING

The mortar fleet, the “ Essex ” and the “ Richmond,” having appeared again below Port Hudson, orders were received on May 9th for a detachment of Co. K to take “ The Baby ” to Troth’s landing and at daylight on the 10th open fire on the fleet. The entire expedition under command of Lieut. Col. DeGournay consisted of one 24-pounder rifled, with a detachment from DeGournay’s battalion; one 4 t 6 q 2 ^ inch brass rifle, detachments from Co. K, First Alabama Regiment; one 20-pounder and one 12-pounder Parrott guns, with detachments from Miles’ Legion.

Colonel William R. Miles was the commander of a regiment known as Miles’ Louisiana Legion, organized in summer, 1862. Troops from this unit engaged Union troops under the command of General C. C. Auger at the Battle of Plains Store, a few miles outside the Port Hudson garrison, on May 21, 1863. On May 22, Miles was named commander of the Confederate units defending the right flank at Port Hudson, which included the Citadel. Being located close to the river and near where the Union fleet operated, his forces were subject to very heavy bombardment from the ships and other enemy batteries throughout the siege. During the Union assault of May 27th, they faced the forces of General Thomas Sherman. On June 14th, the Citadel was attacked by forces under the command of General William Dwight.

Of Co. K there were 17 men, Sergeants Ellis and Royals, gunners, under command of Lieut. Tuttle. Soon after dark on the evening of the 9th a fatigue party began work, and during the night constructed a rude redoubt 12 by 24 feet, sinking it eighteen inches in the ground and throwing the earth to the front, thus forming an open earthwork with a parapet just high enough for the muzzles of the guns to project over. In this were placed the two larger guns, while the two Parrotts were placed in an old battery a few hundred yards lower down. From 11 p. m. till I A. m. the mortars shelled the batteries, but did not discover the working party. Shortly after 4 a. m. the earthwork was completed and the guns were put in position. While the fatigue party were still standing around, the flash and roar of the mortars caused a stampede of the non-combatants. As before, the shells were thrown at the batteries above, showing that the expedition was still undiscovered. The guns were loaded and so soon as it was sufficiently light were aimed at the “ Essex;” then the command rang out “Fire!” The percussion shell from “ The Baby ” striking on the projecting point of land between us and the ‘‘Essex” exploded, the fragments rattling on the iron sides of that vessel. The guns were now loaded and fired as rapidly as possible, being directed at the “ Essex ” and mortar – boats. The latter were, however, moored close under the bluff and were secure except from fragments of bursting shells. As we afterwards learned the surprise of the enemy was complete; it took them but a few minutes, however, to recover, and shells from the mortars soon transcribed a shorter curve, exploding over our guns or burying themselves in the earth around them. Next the eight and nine-inch guns of the “ Essex ” opened, and a few minutes later a 100-pound rifle missile from the “ Richmond ” burst just as it passed the battery. The earth fairly shook as mortars, Columbiads, rifles and bursting shells joined in one continuous roar on that pleasant Sabbath morning. At the twenty-eighth shot, owing to the breaking of a chin-bolt holding on the trunnion-cap, “ The Baby ” was disabled. A few minutes before this the “ Richmond ” moved from her anchorage, and steamed towards the batteries; the last shot from the brass gun went hurtling through her rigging, and the last shot left in the locker of the 24-pounder struck her under the quarter; the Parrotts, from lack of ammunition, or some other cause, had ceased firing, so the batteries were silent. The “ Richmond ” came steadily on until within about 400 yards firing rapidly, then turning and giving in succession both broadsides she steamed back to her anchorage. The fleet now ceased firing and a death-like stillness followed the terrific roar of the battle.

Co. K had one man, Clark, wounded, a fragment of a shell cutting off two of his fingers. One man was mortally wounded and a Lieutenant severely wounded at the Parrott guns. There was also one or two casualties in the infantry support, and a man was killed in one of the regular batteries. The damage to the enemy was trifling; the “Essex” was struck about a dozen times by fragments of shell and once fairly by a solid shot. Four shot hit or passed through the rigging of the “ Richmond.” One of the mortar-boats was struck in the bow and another on the deck by fragments of shells, and it was reported that several of the crews were wounded.

As soon as the firing ceased ropes were attached to the trails of the guns, and they were drawn out of battery, limbered up and taken back to camp. The enemy, curiously, did not re-open fire during the removal, thus showing that they were very willing to have the guns taken away. When the “ Richmond ” was seen to leave her anchorage, Lieut. Pratt with the 30-pounder Parrott started for Battery No. 11, but before he could get there the steamer was out of range.

CLOSE QUARTERS SKIRMISHING

On May 12th and 14th the infantry companies of the regiment were sent to the breastworks in anticipation of an attack, a body of the enemy having cut the railroad between Port Hudson and Clinton.

The Battle of Plains Store or the Battle of Springfield Road was fought May 21, 1863, in East Baton Rouge Parish, Louisiana, during the campaign to capture Port Hudson in the American Civil War. The Union victory closed the last Confederate escape route from Port Hudson. Union cavalry under Brig. Gen. Benjamin H. Grierson, leading the advance of Augur’s division, began skirmishing with Confederate forces under Col. Frank W. Powers. Union infantry approached and the fighting escalated. Col. William R. Miles left Port Hudson at noon, but when he reached the field, Powers’s forces had already retreated and the fighting subsided. Miles nevertheless attacked, and at first succeeded in pushing back the Union infantry. Augur rallied his troops and counterattacked, driving the Confederates from Plains Store and back to the Port Hudson defenses, ending the battle.