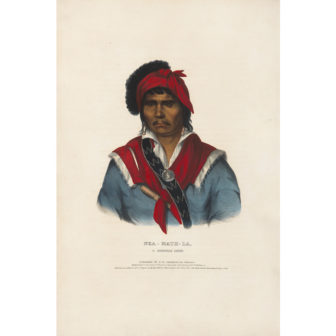

Nehemathla Micco or Neamathia Micco

Creek Chief

The war of 1813 finds him a chief of Atossa, and a partisan of the hostile faction. He was present at the massacre of Fort Mims. After the defeat at the Horse-Shoe, he and Josiah Francis temporarily placed their people on the Catoma, just above the Federal crossing; thence they all went to Florida,

Nothing has been left on record as to the early life of this chief. The war of 1813 finds him a chief of Atossa, and a partisan of the hostile faction. He was present at the massacre of Fort Mims. After the defeat at the Horse-Shoe, he and Josiah Francis temporarily placed their people on the Catoma, just above the Federal crossing; thence they all went to Florida, where the two chiefs became leaders of the hostile Indians, and at last by one act, Neamathla and the Fowltown warriors, all Red Sticks, were defeated in the Battle of Uchee Creek (1813) by the “southern” Creeks.[1]:17 (See Creek War.) They might have won had they not run out of ammunition.[1]:9 When a supply party with ammunition was attacked on its return from Pensacola — a preemptive strike — by U.S. forces, the Red Sticks defeated them at the Battle of Burnt Corn. won an infamous celebrity.

On November 30, 1817, Lieutenant Richard W. Scott, in command of forty United States soldiers, with seven soldiers’ wives and four children, in a large open boat, was slowly ascending the Apalachicola River. They were within a mile of the confluence of the Chattahoochie and the Flint, and were passing along by a swamp densely covered with trees and cane, the boat within a few yards of the shore. Here lay in ambush Nehemathla with a large band of warriors. Not a soul of the whites had the least suspicion of danger. Suddenly the ambushed Indians poured a deadly volley into the closely crowded party on the boat, killing or wounding nearly every man. After firing other volleys, the Indians arose from their ambush, rushed forth, took possession of the boat, and then there took place a horrible scene of indiscriminate killing and scalping. Four men, two of them wounded, made their escape by leaping overboard and swimming to the opposite shore. In twenty minutes the affair was over. The lives of five persons were spared, one being Lieutenant Scott, who was wounded, and one a Mrs. Stuart, the only person unhurt. The five prisoners were bound and carried to a Mikasuki village. Here Mrs. Stuart was given to an Indian, named Yellow Hair, who, it is stated, treated her humanely during all her captivity. But an awful doom, by order of Nehemathla Micco, was reserved for Lieutenant Scott. During the entire day he was subjected to the fire torture in every conceivable form before being put to death. During all this time Nehemathla Micco stood by and enjoyed the prisoner’s agony. The enormity of this act was too great for pardon, and four months later the day of reckoning came. In April, 1814, he and Josiah Francis were both captured and both executed. The torture of Lieutenant Scott was the very charge upon which Nehemathla was hanged by order of General Jackson. An eye witness of the execution described him as “a savage-looking man, of forbidding countenance, indicating cruelty and ferocity. He was taciturn and morose.”

In Buell’s History of Jackson, the first syllable of this chief’s name is elided, and emathla converted into Himallo,—Himollo- micco. In an official letter of General Jackson it is strangely spelled Hornattlemico,—a pen or printer’s slip, perhaps a combination of both. In another letter he spells it Ho- mattlemicco, which excepting the loss of the first syllable closely approaches Nehemathla- micco. General Jackson’s epithet, “the old Red Stick,” shows that he was familiar with his career as a Red Stick during the Creek War.

References. —American State Papers, Mili¬ tary Affairs (1832), vol. i, p. 700; Woodward’s Reminiscences of the Greek or Muscogee In¬ dians (1859), pp. 43, 53, 54, 97; Parton’s Life of Jackson (1861), vol. ii, pp. 430, 431, 455-458; Buell’s History of Jackson (1904), vol. ii, pp. 123-125.