Character of the Formulas–The Cherokee Religion

CHARACTER OF THE FORMULAS–THE CHEROKEE RELIGION

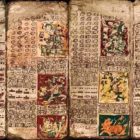

It is impossible to overestimate the ethnologic importance of the materials thus obtained. They are invaluable as the genuine production of the Indian mind, setting forth in the clearest light the state of the aboriginal religion before its contamination by contact with the whites. To the psychologist and the student of myths they are equally precious. In regard to their linguistic value we may quote the language of Brinton, speaking of the sacred books of the Mayas, already referred to:

Another value they have, * * * and it is one which will be properly appreciated by any student of languages. They are, by common consent of all competent authorities, the genuine productions of native minds, cast in the idiomatic forms of the native tongue by those born to its use. No matter how fluent a foreigner becomes in a language not his own, he can never use it as does one who has been familiar with it from childhood. This general maxim is tenfold true when we apply it to a European learning an American language. The flow of thought, as exhibited in these two linguistic families, is in such different directions that no amount of practice can render one equally accurate in both. Hence the importance of studying a tongue as it is employed by natives; and hence the very high estimate I place on these “Books of Chilan Balam” as linguistic material–an estimate much increased by the great rarity of independent compositions in their own tongues by members of the native races of this continent.[1]

The same author, in speaking of the internal evidences of authenticity contained in the Popol Vuh, the sacred book of the Kichés, uses the following words, which apply equally well to these Cherokee formulas:

To one familiar with native American myths, this one bears undeniable marks of its aboriginal origin. Its frequent puerilities and inanities, its generally low and coarse range of thought and expression, its occasional loftiness of both, its strange metaphors and the prominence of strictly heathen names and potencies, bring it into unmistakable relationship to the true native myth.[2]

These formulas furnish a complete refutation of the assertion so frequently made by ignorant and prejudiced writers that the Indian had no religion excepting what they are pleased to call the meaning less mummeries of the medicine man. This is the very reverse of the truth. The Indian is essentially religious and contemplative,

[1. Brinton, D. G.: The books of Chilan Balam 10, Philadelphia, n. d., (1882).

2. Brinton, D. G: Names of the Gods in the Kiche Myths, in Proc. Am. Philos. Soc., Philadelphia, 1881, vol. 19, p. 613.]

and it might almost be said that every act of his life is regulated and determined by his religious belief. It matters not that some may call this superstition. The difference is only relative. The religion of to-day has developed from the cruder superstitions of yesterday, and Christianity itself is but an outgrowth and enlargement of the beliefs and ceremonies which have been preserved by the Indian in their more ancient form. When we are willing to admit that the Indian has a religion which he holds sacred, even though it be different from our own, we can then admire the consistency of the theory, the particularity of the ceremonial and the beauty of the expression. So far from being a jumble of crudities, there is a wonderful completeness about the whole system which is not surpassed even by the ceremonial religions of the East. It is evident from a study of these formulas that the Cherokee Indian was a polytheist and that the spirit world was to him only a shadowy counterpart of this. All his prayers were for temporal and tangible blessings–for health, for long life, for success in the chase, in fishing, in war and in love, for good crops, for protection and for revenge. He had no Great Spirit, no happy hunting ground, no heaven, no hell, and consequently death had for him no terrors and he awaited the inevitable end with no anxiety as to the future. He was careful not to violate the rights of his tribesman or to do injury to his feelings, but there is nothing to show that he had any idea whatever of what is called morality in the abstract.