CHEROKEE INDIAN TRIBE OF ALABAMA

Cherokee Indian Tribe of Alabama

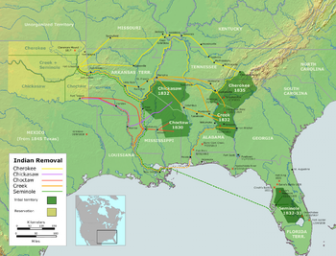

Alabama became part of the Cherokee homeland only in the last quarter of the eighteenth century. Nevertheless, this population of Native Americans significantly contributed to the shaping of the state’s history. Their presence in Alabama resulted from a declaration of war against encroaching white settlers during the American Revolution era. A few decades later, the Cherokees served as valuable allies of the United States during the Creek War of 1813-14. Although the Cherokees fought alongside the United States under Gen. Andrew Jackson, he later campaigned for their removal from the Southeast. Land hunger among whites led to the Indian Removal Act of 1830, which in 1838 resulted in the forced removal of the Cherokees to Indian Territory west of the Mississippi River.

Source: Encyclopediaofalabama.org

Of the Cherokee, Albert James Picket wrote:

The Cherokees were of middle stature, and of an olive color, but were generally painted, while their skins were stained with indelible ink, representing a variety of pretty figures. According to Bartram, the males were larger and more robust than any others of our natives, while the women were tall, slender, erect, and of delicate frame, with features of perfect symmetry. With cheerful countenances, they moved about with becoming grace and dignity. Their feet and hands were small and exquisitely shaped. The hair of the male was shaved, except a patch on the back part of the head, which was ornamented with beads and feathers, or with a colored deer’s tail. Their ears were slit and stretched to an enormous size, causing the persons who had the cutting performed to undergo incredible pain. They slit but one ear at a time, because the patient had to lie on one side forty days for it to heal. As soon as he could bear the operation, wire was wound around them to expand them, and when they were entirely well they were adorned with silver pendants and rings.

Many of them had genius, and spoke well, which paved the way to power in council. Their language was pleasant. It was very spirited, and the accents so many and various that one would often imagine them singing in their common discourse.

They had a particular method of relieving the poor, which ought to be ranked among the most laudable of their religious ceremonies. The head men issued orders for a war dance, at which all the fighting men of the town assembled. But here, contrary to all their other dances, only one danced at a time, who, with a tomahawk in his hand, hopped and capered for a minute, and then gave a whoop. The music then stopped till he related the manner of his taking his first scalp. He concluded his narration, and cast a string of wampum, wire, plate, paint, lead, or anything he could spare upon a large bearskin spread for the purpose. Then the music again began, and he continued in the same manner through all his warlike actions. Then another succeeded him, and the ceremony lasted until all the warriors had related their exploits and thrown presents upon the skin. The stock thus raised, after paying the musicians, was divided among the poor. The same ceremony was used to recompense any extraordinary merit.

The Cherokees engaged oftener in dancing than any other Indian population; and when reposing in their towns, almost every night was spent in this agreeable amusement. They were likewise very dexterous at pantomimes. In one of these, two men dressed themselves in bear-skins, and came among the assembly, winding and pawing about with all the motions of that animal. Two hunters next entered, who, in dumb show, acted in all respects as if they had been in the woods. After many attempts to shoot the bears, the hunters fired, and one of them was killed and the other wounded. They attempted to cut the throat of the latter. A tremendous scuffle ensued between the wounded bruin and the hunters, affording the whole company a great deal of diversion. They also had other amusing pantomimic entertainments, among which was “taking the pigeons at roost.”

Cherokee Indian Bands

Echota Cherokee Tribe of Alabama

The members of the Echota Cherokee Tribe of Alabama are the descendants of those Indian people who escaped the infamous “Trail of Tears” by hiding out in the mountainous backwoods and lowlands of the Southeast. Others fled from the march after it began and others simply walked away and came home after reaching Indian Territory. They kept to themselves, did not speak the language and did not teach it to their children for fear the child might speak it in the presence of someone who would learn the secret of their ancestry. If this happened, they could immediately be taken into custody and sent to Indian Territory in the west. Everything they owned could be given away by the State.

Source: State of Alabama Indian Affairs Commission

Cherokee Indian Clans:

What Are the 7 Cherokee Clans?

Wolf Clan

The “Wolf Clan” or The Aniwaya, has been known throughout time to be the largest clan. During the time of the Peace Chief and War Chief government setting, the War Chief would come from this clan. Wolves are known as protectors. Historically, the Wolf Clan was the largest and most important among the Cheroke

Paint Clan

Commonly called the “Red Paint Clan”. The Aniwodi or the Paint Clan were historically known as a prominent medicine people. Medicine is often ‘painted’ on a patient after harvesting, mixing and performing other aspects of the ceremony.

Deer Clan

The “Deer Clan.” The Aniawi, or Deer Clan, were historically known as fast runners and hunters. Even though they hunted game for subsistence, they respected and cared for the animals while they were living among them. They were also known as messengers on an earthly level, delivering messages from village to village, or person to person.

Bird Clan

The “Bird Clan” or Anitsiskwa, were historically known as messengers. The belief that birds are messengers between earth and heaven, or the People and Creator, gave the members of this clan the responsibility of caring for the birds. The subdivisions were Raven, Turtledove, and Eagle, probably in origin three separate clans later consolidated into one. Earned Eagle feathers were originally presented by the members of this clan, as they were the only ones able to collect them.

Wild Potato Clan

“Anigatogewi” cannot confidently be translated; however, this clan is known as the “Wild Potato Clan”, or occasionally as the “Blind Savannah Clan.

The Anigatogewi’s only subdivision was Blind Savannah, possibly a separate clan in origin. Historically, members of this clan were known to be ‘keepers of the land,’ and gatherers. The wild potato was a main staple of the traditional Cherokee life in the Southeast (Tsalagi Uweti).

Long Hair Clan

“Long Hairs” or “Twisters.” The name can be translated as “They have just become offended.” or could be short for Gitlugunahita, which means literally “Long Hair”.

The Anigilahi or the Long Hair Clan, whose subdivisions were Twister, Wind, and Strangers (possibly separate clans in origin combined into one), were regarded as peacemakers. Peace Chiefs would often be from this clan. In the times of the Peace Chief and War Chief government, the Peace Chief would come from this clan. Prisoners of war, orphans of other tribes, and others with no Cherokee tribe were often adopted into this clan, thus a common interpretation of the name ‘Strangers.’

Blue Clan

This is The Anisahoni, or Blue Holly Clan, subdivisions were Panther, or Wildcat, and Bear, probably in origin two separate clans that were later consolidated with a third. Historically, this clan produced many people who were able to make special medicines for the children. The medicine was made from a blue plant which is where the clan gained its name.

Cherokee Indian Communities:

Where did the Cherokee live in Alabama?

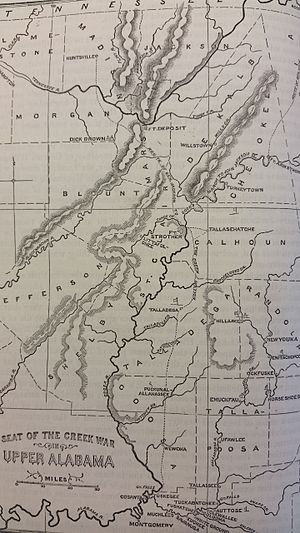

Benjamin Hawkins and the Creek Indians: By 1800 many Cherokees lived on dispersed farmsteads in northeast Alabama. They established communities at Turkey Town, Wills Town, Sauta, Brooms Town, and Creek Path at Gunter’s Landing, all of which provided leadership within the Cherokee Nation.

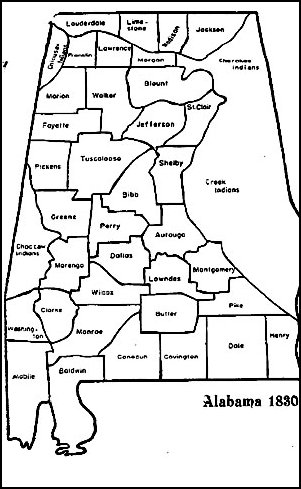

By 1782, the Cherokees had begun to establish settlements in what is now northeast Alabama in present-day Madison, Jackson, Marshall, DeKalb, Cherokee, and Etowah Counties and even as far west as Colbert County.

During the war, the Chickamauga, a pro-British faction of Cherokees, split from the Upper Towns on the Little Tennessee and Hiwassee Rivers in east Tennessee. Led by war chief Dragging Canoe and supported by British agents and sympathetic traders, the Chickamauga left to establish towns farther down the Tennessee River. Two of these, Long Island Town and Crow Town, were located on the river near present-day Bridgeport, Jackson County. By 1800 many Cherokees lived on dispersed farmsteads in northeast Alabama. They established communities at:

Crow Town

Crow Town (trans, of Kâgûnyĭ, ‘crow place’, from kâgû ‘crow’, yĭ ‘locative’). A former Cherokee town on the left bank of Tennessee r., near the mouth of Raccoon cr., Cherokee co., N. E. Ala. It was one of the so-called “five lower towns” built by those Cherokee, called Chickamauga, who were hostile to the American cause during the Revolutionary period, and whose settlements farther up the river had been destroyed by Sevier and Campbell in 1782. The population of Crow Town and the other lower settlements was augmented by Creeks, Shawnee, and white Tories until it reached a thousand warriors. The towns were destroyed in 1794. See Mooney in 19th Rep. B. A. E., 54, 1900.

Turkey Town

The Native American settlement of Turkeytown (Cherokee: “Gun’-di’ga-duhun’yi”), sometimes called “Turkey’s Town”, was named after the original founder of the settlement, the Chickamauga Cherokee chief, Little Turkey. Turkeytown was settled in 1788. The town was established by Little Turkey during the Cherokee–American wars as a refuge for him and his people from the hostilities then being engaged in between the Cherokee and the American frontiersmen.

At one point in history, this seemingly inconspicuous village stretched for approximately 25 miles along both banks of the Coosa River, and became the largest of the contemporary Cherokee towns.

The American community of Turkey Town developed around the Cherokee town Turkeytown. A post office called Turkey Town was established in 1828, and remained in operation until it was discontinued in 1861. The community was named after the village, which was named in honor of the Cherokee chief Little Turkey.

Turkeytown was the original site of the US military outpost of Fort Armstrong (later titled Fort Lovell) established in December of the year 1813 as an ongoing protection for the area, and originally garrisoned entirely by Cherokee soldiers.

An interesting story, “Fort Turkeytown location remains an Etowah mystery.”

Wills Town

Willstown (sometimes Wattstown or Titsohili) was an important Cherokee town located in the southwesternmost part of the Cherokee Nation (in present-day DeKalb and Etowah counties in Alabama) prior to the Indian removal. It was commonly called “Willstown” after its headman, a red-headed man of mixed-race named Will Weber (also known as “RedHead Chief Will”), who was famous for his mane of thick red hair.

The town, which had sometimes also been called Wattstown because Chickamauga leader, John Watts, had used it as his headquarters, was founded during the Cherokee–American wars, and served as the council seat of the Lower Cherokee well into the 19th century. According to Major John Norton, a more accurate transliteration would have been Titsohili. He had stayed at Willstown several times.

Willstown was part of the Native American trade network in the region. The settlement of Willstown began at the southernmost perimeter of Lookout Mountain near the banks of Lookout or Little Wills Creek. Willstown sat in the present right-of-way of the Great Southern Railroad; bordered to the northwest by an ancient Indian trade path or trail. Willstown was one major trade center along the trade path. The trail, which coincides with the current route of US Highway Eleven since the 1920s, ran through what is now Attalla, Alabama, and continued north along the edge of the mountains through what is now Reece City, Crudup, Keener, Collinsville, Killian, and Fort Payne into Valley Head and the old mining settlement of Battelle.

There are three known Indian trading sites along the stretch between Attalla and Collinsville, as well as numerous burial sites, home-sites and remnants of farms.

Wikipedia contributors, “Willstown (Cherokee town),” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Willstown_(Cherokee_town)&oldid=823524572 (accessed June 3, 2018).

Sauta

Not many records exist concerning Sauta but there is an article about Ancient Sauta Town at this website.

Brooms Town

Long Island Town

Creek Path at Gunter’s Landing

Did Cherokees Live in Teepees?

The Cherokee never lived in tipis. Only the nomadic Plains Indians did so. The Cherokee were southeastern woodland Indians, and in the winter they lived in houses made of woven saplings, plastered with mud and roofed with poplar bark. … Today the Cherokee live in ranch houses, apartments, and trailers.

Indian Removal Act

While the Indian Removal Act made the move of the tribes voluntary, it was often abused by government officials. The best-known example is the Treaty of New Echota. It was negotiated and signed by a small faction of Cherokee tribal members, not the tribal leadership, on December 29, 1835. It resulted in the forced relocation of the tribe in 1838. An estimated 4,000 Cherokee died in the march, now known as the Trail of Tears.

Missionary organizer Jeremiah Evarts urged the Cherokee Nation to take their case to the U.S. Supreme Court. The Marshall court ruled that while Native American tribes were sovereign nations (Cherokee Nation v. Georgia, 1831), state laws had no force on tribal lands (Worcester v. Georgia, 1832).

In spite of this acculturation, many white settlers and land speculators simply desired Indian lands. Some claimed that Indian presence was a threat to peace and security; some U.S. states, like Georgia, passed laws that prohibited whites from living on Native American territory without a license from the state (e.g., an 1830 Georgia law, taking effect March 31, 1831). The Georgia law has been described as being written to justify removing white missionaries who were helping the Native Americans resist removal.

The Cherokee Indians have had continuing dealings with the U.S. Government since the 1700’s through treaties, legislation, and the courts. There are probably more federal records concerning the Cherokees than any other tribe. During the 1830’s and 1840’s, the period covered by the Indian Removal Act, many Indians were forced to remove to what is now Oklahoma. A small number of Indians remained in the southeast and gathered in the North Carolina area where they purchased land and continued to live on the Quala Boundary. Many went into the Appalachian Mountains to escape the removal.

Cherokee Ancestry Research

Cherokee Ancestry falls into three main groups:

1) Persons listed on the final roll of the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma that were closed in 1907 and their descendants.

2) Persons enrolled as members of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians of North Carolina and their descendants, Baker Roll.

3) Other persons of Cherokee Indian ancestry.

The first groups were those Cherokees who went West and formally organized as the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma. After about a half-century of self-government, a law enacted by Congress in 1906 directed that a final roll be made and each enrollee be given an allotment of land or be paid cash. After that date no names could be added to the final rolls. The 1906 enrollment records are kept by the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

The second group, or Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians of North Carolina, are formally organized and have their own requirements for member ship.

Information about the Indian ancestry of persons in the third group of Cherokees is the most difficult to locate. Some of these Indians did not sign up when necessary. The information for this group is best found by using the same methods as used in compiling ancestries of non-Indians. The claims that were filed in 1906 and were rejected provide the same good source of information that is helpful in tracing Indian ancestry.

1. The different Census Rolls are given control numbers by the National Archives so they may be ordered, such as M-1234. The rolls are usually named for the person taking the census. Each roll pertains to a particular year so it is important to select the year that applies to the individual whom you are looking to find. I usually like to start with the Guion Miller Roll. The claims had to be on file by August 31, 1907. In 1909 Miller stated that 45,847 separate applications had been filed representing a total of about 90,000 individuals; 3436 resided east, and 27,384 were residing West of the Mississippi.

The Eastern Cherokee Claims, also known as the Miller Roll is an excellent source of information. Microfilm M-65 lists the persons name and whether their claim was accepted or rejected, and where they were living at the time they filed the application. Roll 1 is the index. These rolls list their ancestors, as far back as four to six generations, or before 1835. They were taken in 1906 when Cherokees lived all over the United States. They were trying to prove they or their ancestors lived in the Cherokee Nation East in 1835. At that time the Cherokee Nation was Comprised of all or part of the following counties of these states:

Alabama: Blount, Calhoun, Cherokee, Cleburne, Dekalb, Etowah, Jackson, and Marshall County.

1924 BAKER ROLL (East) – The Baker Roll has names, addresses, age, and relationship to the head of household. There were some who were added to the roll by the Indian Office in 1931.

1896 CENSUS (West) – The census takers were cautious to be sure before enrolling anyone as a citizen. Oftentimes they had to swear someone in, and question their information if doubtful. They were to mark Citizen, Shawnee, Delaware, or Freedmen. If in doubt they could contact the 1880 Census with regard to age and name. The census roll gives the name, age, sex, how far they live from the precinct, the degree of blood, and remarks. If they were white they were requested to give which state they were born in.

1896 PAYMENT ROLL (West) – This roll is a record of payment to those whose names appeared on the 1851 Old Settlers list. These were people who went west before the Treaty of 1835. It lists their name, place of residence, age, and the amount of money they received. If the person was deceased, it names the heirs of the individual that received the money.

CHEROKEE CENSUS OF 1880 (West) – This census consists of six schedules for each of the nine Cherokee Districts: Canadian, Cooweescoowee, Delaware, Flint, Going Snake, Illinoise, Saline, Sequoyah, and Tahlequah. Schedule 3 for the Cooweescoowee is incomplete. Information listed on the schedules include the names of persons, their age, sex, nativity, marital status, and occupation. Family relationships are given in the remarks column. The 1880 Census was used as a basis for payment of $16.55 for breadstuff.

1884 HESTER ROLL (East) – Begun in 1882 by Joseph G. Hester this roll is a census of the Eastern Cherokee. It was completed and submitted to the Secretary of the Interior in 1884. There are 2,956 people listed on this roll. The Hester Roll gives the persons, place of residence, city or county, state, previous ancestors who may have been on the roll, their Hester Roll number, and their Chapman, Siler, Swetland, and Mullay Roll number if they have one. The Hester Roll is indexed.

1851 DRENNEN ROLL (West) – This roll contains the names of people that went to Oklahoma after 1835. The roll was taken by John Drennen. The people on this roll were sometimes referred to as Immigrant Cherokees. They lived along the boundaries of Oklahoma.

1851 SILER ROLL (East) – This roll was taken by David W. Siler in accordance with instructions from the Bureau of Indian Affairs. This roll was taken to provide a basis for distributing money due to members of the tribe under the treaty of 1835. The roll is arranged by county and state. It provides information on the roll number, name, age, sex, and race. There were 88 names added to the Siler Roll in 1854 by an Act of Congress. There were 370 families on the Siler Roll.

1852 CHAPMAN ROLL OF EASTERN CHEROKEES – This roll is a receipt roll for a per capita payment made to the Eastern Cherokees listed on the Siler Roll. Alfred Chapman disbursed the money. The numbers correspond exactly to the Siler Roll Through number 883. The roll contains the names of the individuals paid, their age, And their relationship to the head of household. It also lists the total amount paid to The head of household or their authorized representative, the date of payment and the witness to the payment.

1848 MULLAY ROLL (East) – The Mullay Roll was taken in 1848 by Special Agent J. C. Mullay authorized by an act of Congress. He was to list the names of the Cherokee Indians who remained East of the Mississippi River after the majority of the tribes moved west under the unhonored Treaty 1835. The Secretary of the Treasury was authorized to set aside $53.00 for each individual wishing to migrate to Indian Territory. The enrollment number lists the names numerically. The remarks column tells their age and relationship to others on the roll. There are approximately 1532 names on the Mullay Roll. The Mullay Roll is not indexed.

1835 HENDERSON ROLL – Daniel Henderson took this census in 1835. It is an accounting to Cherokee Indians and mixed bloods that were living in these states: Tennessee, Georgia, Alabama, and North Carolina. The roll lists many categories. The Most significant are:

*Residence by county and state.

*Male’s ages listed as either under or over 18.

*Female ages listed as either under or over 16.

*How many whites were in each household by marriage.

There is a complete alphabetical index for this roll.

1817-1819 RESERVATIONS – The Treaty of 1817 gave every head of any Indian family residing on the east side of the Mississippi 640 acres of land that by treaty was surrendered to the United States. If any of the heads of families for whom the reservation should be made, should be removed from there, their right were to revert to the United States, and it stipulated that a census of those desiring reservations and consequently citizenship was to be taken and filed in the office of the Cherokee agency. Some reservations were given Life and were given Fee Simple. Twenty-Three were given in Georgia. 2. The Dawes Roll of 1906 is another good source of information. In the following paragraph my grandfather is used as an example.

FINAL ROLL (T-529) – In 1898 by an Act of Congress a commission was established to negotiate agreements with the Five Civilized Tribes: the Cherokees, Choctaws, Chickasaws, Creeks and Seminoles. This was to provide for the dissolution to the tribal governments and the allotment of land to each tribal member. The Commission received applications for membership from more than 250,000 people of which more than 101,000 were enrolled. The tribal membership rolls were closed in 1907. Congressional Act enrolled an additional 312 persons in 1914.

The card census number refers to a Census Card. The information given for each applicant includes name, roll number, age, sex, degree of Indian blood, and their relationship to the head of the household. There are approved, rejected, and doubtful cards.

Check the index, (Roll 1), for the person your are looking for. As an example, we will use my grandfather William Coats. William Coats number is 28090. After you get the number, continue past the index, and you will come to the information about the person. When the number is found, in this case 28090 it lists William Coats, 42, m, ¼, Card Census 4173. Copy the card census number and go to the Enrollment Card Census Roll, (M-1186). There are 93 rolls 1-23 are Cherokees by blood and Cherokee by marriage, rolls 24-38 are Cherokee freedmen, rolls 39-66 are Choctaws, rolls 67-76 are Chickasaws, rolls 77-91 are Creeks, and 92-93 are Seminoles. You will find that number 4172 is on reel 6. This microfilm document copy will look like page number 27 in this newsletter. The number 4173 is in the upper right of the card. The Car Census is a most valuable source of information. It lists the person, their wife and children, their mother and father, as well as what page number they can be found on the 1880 and 1896 census rolls. Each relatives Dawes Roll number is given, along with the Tribal Enrollment year, district, and district number.

3. Other relevant rolls such as the 1986 Census, 1880 Census, 1851 Census, and 1835 Census Rolls are explained in more detail in following sections.

4. Another good source is the book left to the Cherokee people by Emett Starr, History of the Cherokee Indians. Most libraries have this book. Not enough can be said in appreciation for Dr. Emett Starr (1870-1930); for his devotion, from what he left his people. In my opinion, he deserves as much recognition as Sequoyah. Without his book it would be almost impossible to go beyond 1835. He gives a good history in the front of his book, and then the genealogy of the old families. The Eastern Cherokee Claims can be used to connect up with the History of the Cherokee Indians. The claim show on page 28 of the newsletter corresponds with page 311 in Dr. Starrs book, which allowed me to trace my line back to 1726. Emett Starr’s notes are in the Oklahoma Historical Room, in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma.

5. Microfilm number M-208 (Cherokee Agency in Tennessee) – These are the earliest records available at National Archives. This covers the period 1801-1835.

6. Microfilm number M-234 – These are a lot of letters written to the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

7. American State Papers are another excellent source of information. I was able to find a letter written about Samuel Martin in theses. Indian Affairs volume 1 & 2. There are some records in most courthouses in counties where the Indians lived mainly in Tennessee, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, and Alabama.

8. The Tennessee State Archives has many records that Penelope Allen bought from John Ross’s grandson, William Ross. They are available for research.

9. Moravian Mission Records – Early missionaries established a mission among the Cherokees in 1817

So You Have An Ancestor Who Was A Cherokee

Frequently, people are discovering their Cherokee ancestry. Many times, our elders have not passed this information along, and it is only as they are passing to the next world do they talk about their parents and grandparents– their roots.

In the early part of this century, there were many reasons for leaving your Native ancestry unclaimed. In those days a “guardian” was assigned to full-blooded Native Americans to manage their affairs. Many times the “guardian” benefited more than the Indian did. Voting was a privilege denied Native Americans and women until 1924. Women were discouraged from registering by their Anglo husbands, especially if they were living outside the Indian Territory. Probably the most fearful reason was the removal of the Native Americans to Oklahoma Territory. The reasons varied, yet all had merit to the Native American at that time in history.

In 1976, Cherokee voters ratified a new Cherokee Constitution, which changed the ways of measuring tribal membership. At that time, it was determined that anyone who could trace direct descent from the Dawes Rolls, a census taken between 1902-1907, could become a registered citizen of the Cherokee Nation. There are now over 165,00 registered Cherokee citizens.

It does not matter if you are rediscovering your ancestry, or fulfilling a long-time wish of “getting registered.” It is important that you do something now.

Finding Your Cherokee Ancestor

I. Did your ancestor reside in the North Carolina /Tennessee area?

A. If yes, is his/her name on any roll in Cherokee Roots by Bob Blankenship?

1. If yes, contact the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, PO Box 455, Cherokee NC 28719

B. If no, are they on the Guion Miller general index (m-1104, roll)?

1. If yes, follow references from Miller records on M-685 to Drennen or Chapman Rolls (M-685, Roll 12)

2. If no, they are on the “Intruder” lists? (7RA-53 and 7RA-55)

a. If yes, they were not recognized as Cherokee citizens.

b. If no, check the 1896 Old Settler Payment Roll (T-985)

1. If yes, check Old Settler roll of 1851 (M-685, roll 12)

a. Check History of the Cherokee Indians by Emmet Starr

2. If no, your ancestor may be Cherokee but it is unlikely they are on any roll.

II. Did your ancestors live in Oklahoma between 1893 and 1906?

A. If yes, are they on the Dawes Rolls? (Microfiche M-1186, roll 1)

1. If not on the Dawes Rolls, are they on the Guion Miller general index (M-1104, roll)?

a. If yes, follow references from Miller records on M-685 to Drennen or Chapman Rolls (M-685, Roll 12). You can get a copy of someone’s application by sending the application number to: National Archives (NNFJ), Washington, D.C., 20408

b. If no, are they on the “intruder ” lists? (7RA-53 and 7RA-55).

1. If yes, they were not recognized as Cherokee citizens. 2. If no, check the 1896 Old Settler Payment Roll (T-985).

a. If yes, check Old Settler Roll of 1851 (M-685, roll 12).

1. Check History of the Cherokee Indians, by Emmet Starr.

b. If no, your ancestor may be Cherokee but it is unlikely they are on any Roll.

2. If yes, (they were listed on the Dawes Rolls) note their enrollment number and category and find their enrollment card on M-1186.

3. Then use the information on enrollment card to search earlier rolls such as 1896 Census (7RA-19) and 1880 Census (7RA-07).

4. Then check M-1301 for enrollment packet.

5. Is this a direct ancestor?

6. If yes, you maybe eligible for registration. Contact Cherokee Nation, Tribal Registrar, P.O. Box 948, Tahlequah, OK 74465-0948 (918) 456-0671 or Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, P.O. Box 481, Cherokee, NC 28719 (704) 497-5601/5112 or United Keetoowah Cherokee Council, P.O. Box 1329, Tahlequah, OK 74464 (918) 234-3434.

7. Other resources include National Archives and Records, General Services Administration, Washington, D.C. 20408, National Archives (Southeast Region), 1557 Saint Joseph Street, East Point, GA 30344 and The Church of Jesus of Latter Saints, 50 East North Temple Street, Salt Lake City, UT 84150

Visit the author’s www.cherokeeblood.com for a series of books about the Cherokee Indians of Alabama.

Return to Native American Tribes Of Alabama Index

My Great Grandmother (several generations removed) was Cherokee. She was born in 1743, possibly in Alabama. She married my Great (several generations removed) in 1778 and they had 2 sons. She died 1789 in Illinois.

Her name was Wakema Juanita George. His name was William Henri DeShazer. I want more info about Wakema. I am proud to have 1/64th Cherokee blood and want so much more knowledge about that part of my ancestry. When I first discovered her, she was listed as “a Cherokee women”! I was incensed that they did not give her a name. It took me years to finally find it and now I want more. Sharon Richards-Chriest

Joseph F. Stafford, wife Maggie Mae Stafford (Cherokee). General index 28158 or 10449. Maggie is my Great-Grandmother died in 1967 in Samson, Al.