ALABAMA NATIVE AMERICAN TRIBES INDEX

NATIVE AMERICAN TRIBES of Alabama

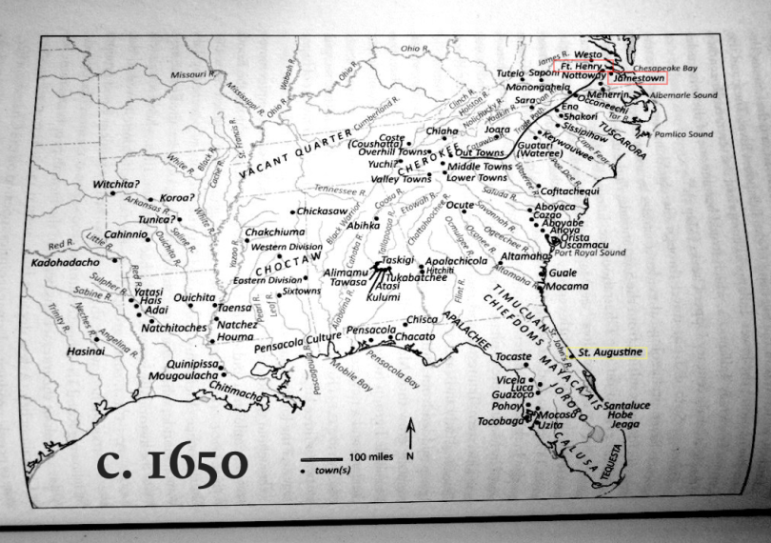

This map, from Robbie Ethridge’s From Chicaza to Chickasaw: The European Invasion and the Transformation of the Mississippian World, 1540-1715, is shocking to the eye. Few (U.S.) Americans have seen historical maps in which indigenous and colonial settlements are treated equally. (The three European towns are highlighted with red (English) and yellow (Spanish) rectangles, which I have added.) Few of us realize the vastness of the inhabited landscape of North America prior to its colonization by Europeans. History is written, and geography is mapped backward from the present to tell the story of inevitable colonial and post-Independence expansion of the United States. Without this perspective, it can seem as if history began with the arrival of European colonists, sidelining stories that predate their settlement, up to and including the vast trade in enslaved native peoples that flourished from 1685 to 1715.

Credit: Carwil without Borders

Native American History in Alabama

When Andrew Jackson became president of the United States in 1829, his government took a hard line. Jackson abandoned the policy of his predecessors of treating different Indian groups as separate nations. Instead, he aggressively pursued plans against all Indian tribes which claimed constitutional sovereignty and independence from state laws, and which were based east of the Mississippi River. They were to be removed to reservations in Indian Territory west of the Mississippi (now Oklahoma), where their laws could be sovereign without any state interference.

At Jackson’s request, the United States Congress opened a debate on an Indian Removal Bill. After fierce disagreements the Senate passed the measure 28–19, the House 102–97. Jackson signed the legislation into law May 30, 1830.

Alphabetical List of Native American Tribes in Alabama

Abihka Tribe

A branch of the Muskgoee & Creek Confederacy. The members of the Abihka were Upper Creek Indians. Their main place of residence was along the banks of the Coosa and Alabama rivers, in what is now Talladega County, Alabama.

Alabama Tribe

This tribe belonged to the Muskhogean Tribe which was the Southern Division. The Native word is “Albina” which means to camp.

The Alabama or Alibamu (Alabama: Albaamaha) are a Southeastern culture people of Native Americans, originally from Alabama. They were members of the Muscogee Creek Confederacy, a loose trade and military organization of autonomous towns; their home lands were on the upper Alabama River.

The Alabama and closely allied Coushatta people migrated from Alabama and Mississippi to the area of Texas in the late 18th century and early 19th century, under pressure from European-American settlers to the east. They essentially merged and shared reservation land. Although the tribe was terminated in the 1950s, it achieved federal recognition in 1987 as the Alabama-Coushatta Tribe of Texas. 1

- Wikipedia contributors, “Alabama people,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Alabama_people&oldid=840285082 (accessed June 11, 2018).

Apalachee Tribe

A part of this tribe lived for a time among the Lower Creeks and perhaps in this State. Another section settled near Mobile and remained there until West Florida was ceded to Great Britain when they crossed the Mississippi.

Apalachicola Tribe

Very early this tribe lived on the Apalachicola and Chattahoochee Rivers, partly in Alabama. Sometime after 1715 they settled in Russell County, on the Chattahoochee River where they occupied at least two different sites before removing with the rest of the Creeks to the other side of the Mississippi.

Atasi Tribe

A sub-tribe of the Muskgoee.. At least three successive places were occupied by the Atasi on Tallapoosa River. The first was some miles above the sharp bend in the river at Tukabahchee, where Bartram found them in 1777-78. 4 The second was five miles below Tukabahchee on the south side of the river, 5 and the third a few miles higher on the north side near the mouth of Calebee Creek. The name appears in the census lists of 1738, 1750, 1760, and 1761. 6 On the last mentioned date James McQueen and T. Ferryman were the officially recognized traders. 7

| 4. |  |

Bartram, Travels, p. 448 et seq. |

| 5. |  |

Ga. Hist. Soc. Colls., IX, pp. 40, 46. ” On the opposite bank [from Mr. Bailey’s house] formerly stood the old town Ohassee [Ottassee], a beautiful rich level plane surrounded with hills, to the north, it was formerly a canebrake, the river, makes a curve round it to the south, so that a small fence on the hill side across would enclose it.”- p. 40. |

| 6, 7. |  |

MSS., Aver Lib.; Miss Prov. Arch., I, p. 95; Ga. Col. Docs., VIII, p. 523. |

Biloxi Tribe

The Biloxis are original people of the American southeast, inhabiting the southern parts of Mississippi and Alabama. After a smallpox epidemic killed many of the Biloxi people, the survivors moved west and joined their allies the Tunicas in Louisiana.

See Wikipedia contributors, “Biloxi people,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia and Biloxi Indian Fact Sheet.

Additional References: Frederick Webb Hodge, in his Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico, gave a more complete history of the Tunica-Biloxi tribe, with estimations of the population of the tribe at various time periods. Additional details are given in John Swanton’s The Indian Tribes of North America.

History of the Indian Tribes of North America

Chatot Tribe

This tribe settled near Mobile after having been driven from Florida and moved to Louisiana about the same time as the Apalachee.

A tribe or band which French settled south of Ft. St. Louis, Mobile Bay, Alabama, in 1709. Bienville wishing to change his settlement, ” selected a place where the nation of Chatot were residing, and gave them exchange for it a piece of territory fronting on Dog River, 2 leagues farther down”. 1. According to Baudry des Lozieres 2 the Chatot and Tohome tribes were related to the Choctaw and spoke the French and Choctaw languages.

Penicaut,1709, in French, Hist. Coll. LA 1, 103, 1869

Baudry des Lozieres, Voy., 1794

Cherokee Tribe

All were living east of the Mississippi as they had for thousands of years. In the latter part of the eighteenth century some Cherokee worked their way down the Tennessee River as far as Muscle Shoals, constituting the Chickamauga band. They had settlements at Turkeytown on the Coosa, Willstown on Wills Creek, and Coldwater near Tuscumbia, occupied jointly with the Creeks and destroyed by the Whites in 1787. All of their Alabama territory was surrendered in treaties made between 1807 and 1835.

The Indian Removal Act of 1830 implemented the U.S. government policy towards the Indian populations, which called for moving Native American tribes living east of the Mississippi River to lands west of the river. While it did not authorize the forced removal of the indigenous tribes, it authorized the President to negotiate land exchange treaties with tribes located in lands of the United States.

There are four Cherokee state recognized groups:

Echota Cherokee Tribe of Alabama

United Cherokee Ani-Yun -Wiya Nation

Cherokee Tribe of Northeast Alabama

Cher-O-Creek Intratribal Indians, Inc.

Chickamauga Cherokee Tribe (Lower Cherokee)

Chickasaw Indians

The Chickasaw Indians traditionally lived in what is now northwestern Alabama, northern Mississippi, and southwestern Tennessee. Linguistically, the Chickasaw were closely connected with the Choctaw and one of the principal tribes of the Muskhogean group.

The Chickasaw had a few settlements in northwestern Alabama, part of which State was within their hunting territories. At one time they also had a town called Ooe-asa (Wǐ-aca) among the Upper Creeks.

The meaning of the name Chickasaw is unknown, though the ending suggests that it might have been a place name. Also called:

Ani’-Tsl’ksfl, Cherokee name.

Kasahd dnfl°, Yuchi name.

TchaktchM,n, Arapaho name.

Tchfkasa, Creek name.

Tci’-ka-sa’, Kansa name.

Ti-ka’-jh, Quapaw name.

Tsi’-ka-ca, Osage name.

Choctaw (Chahtas)

The peoples who became known as the Choctaws (they call themselves Chahtas) originally lived as separate societies throughout east-central Mississippi and west-central Alabama. The Choctaw Indians established some 50 towns in present-day Mississippi and western Alabama. With a population of at least 15,000 by the turn of the nineteenth century, the Choctaws were one of the largest Indian groups in the South. Thousands of Choctaws remained in the Southeast even after removal and are known today as the federally recognized Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians and the state-recognized MOWA Band of Choctaw Indians (so named for their location in Mobile and Washington County) Choctaws of Alabama.

Encyclopedia of Alabama offers a superb article on Choctaws in Alabama.

Creek

A confederacy of a number of cultural groups, the Creeks, now known as the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, played a pivotal role in the early colonial and Revolutionary-era history of North America. In 1775, author and trader James Adair described the Creek Indians as “more powerful than any nation” in the American South. Despite the fact that they were able political and economic partners of the colonial and early U.S. government, the Creeks suffered the same fate as their fellow southeastern tribes, and many of them were forced from their lands in the 1830s. Creek culture is kept alive in Alabama among the Poarch Band of Creek Indians, based in Escambia County.

Source: EncyclopediaofAlabama

Eufaula

A subtribe of the Muskogee. The Eufaula people were a tribe of Native Americans in the United States, located in the Southeast. A Muskogean-speaking people, they possibly broke off from the Kealedji or Hilibi tribe.

Some Eufaula lived along the Chattahoochee River in what became the state of Georgia. The Lower Creek Eufaula settled there by 1733, and quite possibly earlier than that. With more frequent contact with Europeans and later Americans, they had trade and adopted some European-style customs.

In 1832, theirs was the only Upper Creek town listed on the census. In 1825 their chief Yoholo Micco traveled to Washington, D.C. in an attempt to renegotiate the Treaty of Indian Springs (1821). They were unsuccessful, and the very disadvantageous Treaty of Indian Springs (1825) was enacted which forced them to move across the river in Eufaula, Alabama, where a bike trail commemorates their story.

In 1832, theirs was the only Upper Creek town listed on the census. In 1825 their chief Yoholo Micco traveled to Washington, D.C. in an attempt to renegotiate the Treaty of Indian Springs (1821). They were unsuccessful, and the very disadvantageous Treaty of Indian Springs (1825) was enacted which forced them to move across the river in Eufaula, Alabama, where a bike trail commemorates their story.

In 1836 they were forced further west again, during the Trail of Tears. Their people were the only Upper Creek town that moved to Indian Territory; they settled near what developed as Eufaula, Oklahoma, named for them and their towns.

Editor: AccessGenealogy.com has more information on the Eufaula Tribe.

Fushatchee Tribe

A division of the Muskogee. Fushatchee were a Muscogee sub-tribe. They were located in Alabama and Florida.

The Fushatchee may have come out of three different Muscogee tribes: Kanhatki, Kolomi, and the Atasi. They were first noted as existing in 1733. Traders tracked them as being in the region from then until 1797. Some traders called them the “Coosahatchies of Swan”. The village is described by trader Hawkins as being on flat land, on the south side of the Tallapoosa River. The tribe grew corn on each side of the river. A ditch was built for fortification. Additional, older settlements were found down the river.

After the Red Stick War, the Fushatchee relocated to northern Florida. They disappeared in census data after 1832. Eventually, the tribe merged with the Kanhatki. They relocated together further west, after the Seminole Wars, and eventually into the Seminole Nation where they settled together. The tribe would be represented by the Seminole. Their village was called Liwahali.

Hilibi

Subtribe of the Muskogee.

Hitchiti

A Muskhogean tribe which branched into Georgia. The Hitchiti were part of the Creek confederacy. After 1715 they moved to Henry County, Alabama, en route to their most well-known location of Chattahoochee County. By 1839, nearly all Hitchit had been relocated to Native American reservations in Oklahoma, where they gradually merged with Creek and other tribes of the Creek Confederacy.

Ispokogi

Kan-hatki Tribe 3

The history of the Kan-hatki or Ikan-hatki (“White ground”) is parallel with that of the Fus-hatchee. They appear on the De Crenay map, in the lists of 1738, 1750, 1760, and 1761, and in those of Bartram, Swan, and Hawkins. 1 In 1761 their officially recognized traders were Crook & Co. Swan gives Kan-hatki as one of two towns occupied by Shawnee refugees, but this statement was probably due to the presence of some Shawnee from the neighboring settlement of Sawanogi. In September, 1797, Hawkins states that the trader here was a man named Copinger. 2 He gives the following account of the town:

E-cim-hut-ke; from e-cim-na, earth, and hut-ke, white, called by the traders white ground. This little town is just below Coo-loo-me, on the same side of the river, and five or six miles above Sam-bul-loh, a large fine creek which has its source in the pine hills to the north and its whole course through broken pine hills. It appears to be a never-failing stream, and fine for mills; the fields belonging to this town are on both sides of the river. 3

Kealedji Tribe 3

A division of the Muskogee.

Kolomi Tribe 3

The earliest mention of Kolomi town is contained in a letter of the Spanish lieutenant at Apalachee, Antonio Mateos, in 1686. A translation of this has been given in considering the history of the Kasihta. The town was then probably on Ocmulgee River, where it appears on some of the very early maps, placed close to Atasi. From the failure of Mateos to mention Atasi it is possible that that town was not yet in existence. From later maps we learn that after the Yamasee war the Kolomi settled on the Chattahoochee. The maps show them in what is now Stewart County, Ga., but Colomokee Creek in Clay County may perhaps mark a former settlement of Kolomi people farther south. The name is often given on maps in the form “Colomino.” 3 Still later they removed to the Tallapoosa, where, as appears from Bartram, they first settled upon the east bank but later moved across. In all these changes they seem to have kept company with the Atasi. Their name appears in the lists of 1738, 1750, 1760, and 1761. In 1761 their officially recognized trader was James Germany. Bartram thus describes the town in 1777:

Here are very extensive old fields, the abandoned plantations and commons of the old town, on the east side of the river; but the settlement is removed, and the new town now stands on the opposite shore, in a charming fruitful plain, under an elevated ridge of hills, the swelling beds or bases of which are covered with a pleasing verdure of grass; but the last ascent is steeper, and towards the summit discovers shelving rocky cliffs, which appear to be continually splitting and bursting to pieces, scattering their thin exfoliations over the tops of the grassy knolls beneath. The plain is narrow where the town is built; their houses are neat commodious buildings, a wooden frame with plastered walls, and roofed with Cypress bark or shingles; every habitation consists of four oblong square houses, of one story, of the same form and dimensions, and so situated as to form an exact square, encompassing an area or court yard of about a quarter of an acre of ground, leaving an entrance into it at each corner. Here is a beautiful new square or areopagus, in the centre of the new town; but the stores of the principal trader, and two or three Indian habitations, stand near the banks of the opposite shore on the site of the old Coolome town. The Tallapoose River is here three hundred yards over, and about fifteen or twenty feet deep; the water is very clear, agreeable to the taste, esteemed salubrious, and runs with a steady, active current.

A little later Bartram called again and has the following to say regarding the trader, James Germany, mentioned above:

[1] called by the way at the beautiful town of Coolome, where I tarried some time with Mr. Germany the chief trader of the town, an elderly gentleman, but active, cheerful and very agreeable, who received and treated me with the utmost civility and friendship; his wife is a Creek woman, of a very amiable and worthy character

· Serrano y Sanz, Doc. Hist., pp. 194–195. . See p. 221. * This form of the name suggests a derivation from kulo, a kind of oak with large acorns, and omin, where there are.” • Bartram, Travels, p. 394. • MSS., Ayer Lib.; Miss. Prov. Arch., 1, p. 94; Ga. Col. Docs., VIII, p. 523. . Bartram, Travels, pp. 394-395.

and disposition, industrious, prudent and affectionate; and by her he has several children, whom he is desirous to send to Savanna or Charleston, for their education, but can not prevail on his wife to consent to it.”

In May, 1797, according to a list compiled by Hawkins, there was no trader in this town, but in a subsequent list, dated September of the same year, he gives William Gregory, who was formerly a hireling of Nicholas White at Fus-hatchee.? Swan (1791) mentions the place, and Hawkins (1799) thus describes it:

Coo-loo-me is below and near to Foosce-hat-che, on the right side of the river; the town is small and compact, on a flat much too low, and subject to be overflowed in the seasons of floods, which is once in fifteen or sixteen years, always in the winter season, and mostly in March; they have, within two years, begun to settle back, next to the broken lands; the cornfields are on the opposite side, joining those of Fooscehat-che, and extend together near four miles down the river, from one hundred to two hundred yards wide. Back of these hills there is a rich swamp of from four to six hundred yards wide, which, when reclaimed, must be valuable for corn and rice and could be easily drained into the river, which seldom overflows its banks, in spring or summer.

They have no fences; they have huts in the fields to shelter the laborers in the summer season from rain, and for the guards set to watch the crops while they are growing. At this season some families move over and reside in their fields, and return with their crops into the town. There are two paths, one through the fields on the river bank, and the other back of the swamp. In the season for melons the Indians of this town and Foosce-hat-che show in a particular manner their hospitality to all travellers, by calling to them, introducing them to their huts or the shade of their trees, and giving them excellent melons, and the best fare they possess. Opposite the town house, in the fields, is a conical mound of earth thirty feet in diameter, ten feet high, with large peach trees on several places. At the lower end of the fields, on the left bank of a fine little creek, Le-cau-suh, is a pretty little village of Coo-loo-me people, finely situated on a rising ground; the land up this creek is waving pine forest.4

The name of this town is wanting from the census rolls of 1832, and there is little doubt that the tradition is correct which states that it was one of those which went to Florida after the Creek war of 1813. A part of the Kolomi people were already in that country, since they are noted in papers of John Stuart, the British Indian agent, dated 1778.8 According to a very old Creek Indian, now dead, Kolomi decreased so much in numbers that it united with Fus-hatchee, and Fus-hatchee decreased so much that it united with Atasi, with which the town of Kan-hatki, to be mentioned below, also combined. But, as we shall see, this can not have been altogether true, though it is an undoubted fact that the towns mentioned were closely united in terms of friendship. While Kolomi is still preserved as a war name very few of the Creeks in Oklahoma remember it as a town.

Koasati Tribe 3

A division of the Muskogee.

Mobile Tribe

A sub-tribe of the Choctaw &/or Chickasaw.

Mukalsa Tribe

A branch of the Choctaw. The word means “friends.”

Muskogee Tribe 3

The Muscogee, also known as the Creek and the Creek Confederacy, are a closely related group of native North American tribes or Indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands. They are originally from a single confederated native land that now comprises southern Tennessee, all of Alabama, western Georgia and part of northern Florida.

Natchez Tribe

One section of the Natchez Indians settled among the the Abihka Creeks near Coosa River after 1731 and went to Oklahoma a century later with the rest of the Creeks.

Napochi Tribe

The nearest connection found was to the Choctaw. They stayed around the Black Warrior River.

Okchai Tribe 3

A division of the Muskogee.

THE OKCHAI Like the Pakana, Adair includes the Okchai among those tribes which had been “artfully decoyed” to unite with the Muskogee, 5 and Milfort says that the Okchai and Tuskegee had sought the protection of the Muskogee after having suffered severely at the hands of hostile Indians. He adds that the former mounted ten leagues toward

the north (of the confluence of the Coosa and Tallapoosa Rivers) and fixed their dwelling in a beautiful plain on the bank of a little river.” 1 Among some of the living Okchai there seems to be a tradition of this foreign origin, but nowhere do we find evidence that they spoke a diverse language. Their tongue may have been a dialect of Muskogee assimilated to the current speech in very ancient times.

This tribe appears on some of the earliest maps which locate Creek towns, such as that of Popple. Their original seats were, as described by Milfort, on the western side of the Coosa some miles above its junction with the Tallapoosa. By 1738, however, a part of them had left that region and moved over upon a branch of Kialaga Creek, an affluent of the Tallapoosa. Another portion evidently remained for a time near their old country, since the census of 1761 mentions “Oakchoys opposite the said [i. e., the French] fort.” 4

After the cession of Mobile and its dependencies to Great Britain these probably reunited with the main body. Okchai are indeed afterwards spoken of in the neighborhood of the old fort, but they appear to have been in reality Okchaiutci, part of the Alabama, whose history has been given elsewhere. The last were probably those “Okchai” who accompanied the Koasati to the Tombigbee shortly after 1763.°

The Okchai proper are not noted by Bartram except under the general term “Fish Pond” Indians, but appear in the lists of Swan 8 and Hawkins’ and in the census rolls of 1832.10 Hawkins has the following description:

Hook-choie; on a creek of that name which joins on the left side of Ki-a-li-jee, three miles below the town and seven miles south of Thlo-tlo-gul-gau. The settlements extend along the creeks; on the margins of which and the hill sides are good oak and hickory, with coarse gravel, all surrounded with pine forest.”

After the emigration they established their square ground on the southern border of the Creek Nation, where it has remained ever since.

A small band is recorded among the Seminoles of northern Florida in 1778.12

Besides Okchaiutci, which was not properly a branch at all, several settlements were given out by this town. The most prominent and probably the most ancient of these was Łåłogålga (“Fish Place”), from which the traders’ name of “Fish Pond” is derived.

1 Milfort, Mémoire, p. 267.

& Schoolcraft, Ind. Tribes, v, p. 262. 1 Plate 4.

“Ga. Hist. Soc. Colls., III, p. 25. 3 MS., Ayer Lib.

10 Senate Doc. 512, 23d Cong., 1st sess., Iv, pp. 4 Ga. Col. Docs., II, pp. 521-523. • See pp. 200–201.

11 Ga. Hist. Soc. Colls., II, p. 37. See p. 203.

12 Copy of MS. in Lib. Cong. 1 Bartram, Travels, p. 462.

297-298.

“Fish Pond” occurs first in Bartram,” but it was often applied to the Okchai Indians generally, and Låłogålga appears first as a distinct settlement in Swan’s list, 1791. Hawkins (1799) describes it thus:

Thlot-lo-gul-gan; from thlot-lo, fish; and ulgau, all; called by the traders fishponds. It is on a small pond-like creek, a branch of Ul-kau-hat-che, which joins Tallapoosa four miles above Oc-fus-kee, on the right side. The town is fourteen miles up the creek; the land about it is open and waving; the soil is dark and gravelly; the general growth of trees is the small hickory; they have reed in the branches.

Hannah Hale resides here. She was taken prisoner from Georgia when about eleven or twelve years old, and married the head man of this town, by whom she has five children. This woman spins and weaves, and has taught two of her daughters to spin; she has labored under many difficulties, yet by her industry has acquired some property. She has one negro boy, a horse or two, sixty cattle, and some hogs; she received the friendly attention of the agent for Indian affairs as soon as he came into the nation. He furnished her with a wheel, loom, and cards, she has an orchard of peach and apple trees. Having made her election at the national council in 1799 to reside in the nation, the agent appointed Hopoithle Haujo to look out for a suitable place for her, to help her to remove to it with her stock, and take care that she receives no insults from the Indians.

In 1796 the traders stationed there were “John Shirley and Isaac Thomas, the first an American, the latter of German parents.”‘4

Evidently this is one of the two Fish Pond towns mentioned in the census list of 1832. There is a square ground of the name in Oklahoma at the present time, but those who formed it were not direct descendants of the people who formed the old Łåłogålga town. When the removal took place all of the Okchai Indians came together and established one square ground near the present Hanna, Okla. Later, as the result of a fission in the tribe brought about by the Civil War, part moved away and settled near Okemah sometime after 1870. There they revived the old term Łåłogålga, which they have since employed.

Asilanabi was founded later than the first Łåłogåiga and was so named because it was first located in a place where Ilex vomitoria was to be gathered. We do not find the name in print until we come to the census rolls of 1832. There is a square ground in Oklahoma so called, but, as in the case of Låłogålga, it has no historical continuity with the older settlement. It is the result of a later fission.

The Okchai living in Oklahoma claim that Potcas hatchee (Hatchet Creek) was a former settlement of theirs which was “lost.” It was in existence in Hawkins’s time and appears in the census list of 1832. The following is Hawkins’s description of it:

Po-chuse-hat-che; from po-chu-so-wau, a hatchet, and hat-che, a creek. This creek joins Coosau, four miles below Puc-cun-tal-lau-has-see, on its right bank; this village is high up the creek, nearly forty miles from its mouth, on a flat bend on the right side of the creek; the settlements extend up and down the creek for a mile. A mile and a half above the settlements there is a large canebrake, three-quarters of a mile through and three or four miles in length.

The land adjoining the settlement is waving and rich, with oak, hickory, and poplar. The branches all have reed; the neighboring lands above these settlements are fine; those below are high, broken hills. It is situated between Hill-au-bee and Woc-co-coie, about ten miles from each town; three miles west of the town there is a small moun. tain; they have some hogs.

Probably the remnants of this town finally reunited with the main body. Two other “lost” settlements are also remembered—Tålså håtchi (Tulsa Creek) and Tcahki tåko (broad shallow ford). This last, however, may have been the Okfuskee village of that name, at one time on Chattahoochee River.2

Okmulgee Tribe

This was a branch of the Creek tribe. A Creek tribe and town of the Hitchiti connection.

Osochi Tribe

It is believed their language was Muskogee but little is known about the meaning of Osochi. The closest relation seems to be with the Chiaha.

Pakana Tribe 3

We now come to peoples incorporated in the Muskhogean confederation which were probably distinct bodies and yet not certainly possessed of a peculiar dialect like the Hitchiti, Alabama, and other tribes of foreign origin already considered. The Pakana are given by Adair as one of those people which the Muskogee had “artfully” induced to incorporate with them, and he is confirmed as to the main fact by Stiggins, whose account of them is as follows:

The Puccunnas at this day are only known by tradition to have been a distinct people and their antient town or habitation is called Puccun Tal ahassee which is Puccun old town. This antient town is in the present Coosa County of this State [Alabama). The Au-bih-kas have a tradition that they were a distinct people and that they in old times were very numerous, but do not say whether they were immigrants or not, or at what time they became one of the national body. But they say as they belonged to the national body one and inseparable there was no distinction made so that by continual intermarriage with the other tribes they at length became absorbed and assimilated with their neighbors without distinction and no other knowledge is left regarding them but the name of their antient habitation. Whether in conversation they had a separate tongue of their own or not tradition is silent.s

1 The Lib. Cong. MS. has “20” in each of these places.

* In his “Letters” he says this village consisted of “6 habitations and a small town house.”-Ga. Hist. Soc. Colls., IX, p. 34.

“Ga. Hist. Soc. Colls., III, pp. 48-49.

* Senate Doc.512, 230 Cong., ist sess., Iv, pp. 327-330.

5 Miss. Prov. Arch., 1, p. 95.

6 Ga. Col. Docs., vm, p. 523.

Senate Doc. 512, 23d Cong., 1st sess., iv, pp. 278-280. . Stiggins, MS., p. 5.

Not much can be added to this. There is a tradition among the modern Creeks that the Pakana separated from the Abihka, but it is evidently due to the proximity of the two peoples in ancient times and the number of intermarriages which took place between them. Again, an old Hilibi man told me that this town was founded by a Wiogufki Indian named Bakna, who held the first busk in his own yard, and whose name became attached to the new town.

Pawokti Tribe

This tribe moved from Florida to the neighborhood of Mobile along with the Alabama Indians and afterward established a town on the upper course of Alabama River. Still later they were absorbed into the Alabama division of the Creek Confederacy.

Pilthlako Tribe

A branch of the Creeks.

Sawokli Tribe

This tribe belonged to the Muskhogean tribe.

Seminole Tribe

Shawnee Tribe

Occupied the Tallapoosa & Sylacauga areas.

Tawasa Tribe

Tawasa Indians (Alibamu: Tawáha).

Locations: Autauga Alabama, Autauga County Alabama

A Muskhogean tribe first referred to by the De Soto chroniclers in the middle of the 16th century as Toasi and located in the neighborhood of Tallapoosa river.

In the early 1500s, the nomadic Tawasa tribe was found by Hernando De Soto, near central Alabama. Almost two centuries later, the Tawasa were ambushed by other tribes, who enslaved and relocated some of them. As for those who were able to get away, many accepted the help of the French and sought freedom in southern Alabama, near Mobile. Around a decade later, the tribe relocated again, near their original location of settlement, in central Alabama. The Tawasa remained where they were for around a century that is, until the Treaty of Fort Jackson, in 1814. After the signing of the treaty, the tribe relocated again, this time northeast of their old establishment, near Wetumpka. The tribe broke apart at that point, with some members joining the Creeks, some joining the Seminoles, and others unaccounted for. Subsequently they moved south east and constituted one of the tribes to which the name “Apalachicola” was given by the Spaniards.

Taensa Tribe

This group came from Louisiana & settled in Mobile.

Toasi Tribe

The Toasi were known to Anglo-Americans as the Tawasee or Tawasa. Apparently, before the French left, they were allied with the Alabama, but then joined the Creek Confederacy afterward.

Tohome Tribe

A division of the Muskogean tribe.

Tukabahchee Tribe

About the same time [as that in which the Muskogee and Alabama finally made peace with each other] an Indian tribe which was on the point of being destroyed by the Iroquois and the Hurons, came to ask the protection of the Moskoquis, whom I will now call Crĕcks. The latter received them among themselves and assigned them a region in the center of the nation. They built a town, which is now rather large, which is named Tuket-Batchet, from the name of the Indian tribe. The great assemblies of the Crĕck Nation, of which it forms an integral part, are sometimes held within its walls. 2

Tukabahchee was not only considered one of the four “foundation sticks” of the Creek Confederacy, but as the leading town among the Upper Creeks, and many add the leading town of the whole nation.

| 2. |  |

Milfort, Mémoire, pp. 265-266. |

Tuskegee Tribe

A branch of the Muskogeans.

Wakokai Tribe 3

Wiwohka Tribe 3

According to tradition, Wiwohka was a made-up or “stray” town, formed of fugitives from other settlements, or those who found it pleasanter to live at some distance from the places of their birth. One excellent informant stated that anciently it was called Witumpka, but the names mean nearly the same thing, “roaring water” and “tumbling water.” Both designations are said to have arisen from the nature of the place of origin of these people, near falls, and these may have been the falls of the Coosa. From the preservation of a purely descriptive name and their comparatively recent appearance in Creek history it may be fairly assumed that they had not had a long existence. Their name appears on the De Crenay map, in the lists of 1738, 1750, 1760, and 1761.’ It is wanting from Bartram’s list, but reappears in those of Swan and Hawkins and in the census rolls of 1832. The census of 1761 couples it with “New Town,” and gives the traders as William Struthers and J. Morgan. The irregular nature of its origin may perhaps be associated with its later responsibility for the Creek war of 1813 and the Green Peach war in Oklahoma, both of which are laid to its charge. At the present time it has so far died away that but few real Wiwohka Indians remain. Its later relations were closest with the Okchai Indians with whom the survivors now busk.

Yamasee Tribe

There was a band of Yamasee on Mobile Bay shortly after 1715, at the mouth of Deer River, and such a band is entered on maps as late as 1744. It was possibly this same band which appears among the Upper Creeks during the same century and in particular is entered upon the Mitchell map of 1755. Later they seem to have moved across to Chattahoochee River and later to west Florida, where in 1823 they constituted a Seminole town.

Yuchi Tribe

This was an older tribe from around the Muscle Shoals area & it is suggested they probably moved toward the East Tennessee area.

The Yuchi people, spelled Euchee and Uchee, are people of a Native American tribe who historically lived in the eastern Tennessee River valley in Tennessee in the 16th century. The Yuchi built monumental earthworks. In the late 17th century, they moved south to Alabama, Georgia, and South Carolina. After suffering many fatalities from epidemic disease and warfare in the 18th century, several surviving Yuchi were removed to Indian Territory in the 1830s, together with their allies the Muscogee Creek.

The Account of Lamhatty

The Account of Lamhatty refers to a document that lists remembrances from a Tawasan Indian known as Lamhatty, who was captured and enslaved by Creek Natives.[4][5] The document was interpreted by historian Robert Beverly, who sat down with Lamhatty to learn about and document his travels and experiences with other tribes. The article includes descriptions of tribes encountered, and mappings of how and where the tribes made settlements.[4] Lamhatty was originally a part of the Tawasa Tribe, however when he was captured he was sold to another tribe known as the Shawnee Indians.[5] Lamhatty stayed with the Shawnee tribe, until he escaped to find refuge with the English, in Virginia.[1] At this time, Lamhatty met Beverly, who then began to break down Lamhatty’s travels.

References

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Swanton, John Reed (1922). Early History of the Creek Indians and Their Neighbors. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 13.

tawasa indians.

- ^ Jump up to: a b “Alabama Indian Tribe | Digital AlabamaDigital Alabama”. digitalalabama.com. Retrieved 2018-11-28.

- ^ Jump up to: a b “Tawasa Indians | Access Genealogy”. Access Genealogy. 2012-04-29. Retrieved 2018-10-08.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Snyder, Christina (2010). Slavery in Indian Country: The Changing Face of Captivity in Early America. p. 67.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bushnell, David (1908). The Account of Lamhatty.

- ^ “Pawokti”. www.native-languages.org. Retrieved 2018-10-15.

Yuchi Tribal Leaders

Timpoochee Barnard

Yuchi Leader. Born one of eight children of a Scots trader, Timothy Barnard, and a Yuchi woman. He was taught the Yuchi dialect of his mother, the English of his father, and the Muscogee dialect of the Creek people since the Yuchi people had been largely exterminated or absorbed by the Creek and Cherokee by the 18th century. Barnard served as the agent of the Lower Creeks in 1793 and 1794 and was one of the interpreters at the Treaty of Coleraine in 1796. In January 1814 Barnard was commissioned major and placed in command of one hundred Yuchi warriors. Barnard fought with the Americans at the Battle of Callabee Creek. He was one of the signatories to the treaty of Fort Jackson in August 1814 which ended the Creek War. In 1818 under General Andrew Jackson he fought in the Seminole War and distinguishing himself in the Battle at Natural Bridge, where was rescued the only survivor of a massacre on the Apalachicola River. He took a Creek wife and settled near the Creek Agency on the Flint River in present day Georgia where he fathered six children. In 1825 Chief McIntosh of the Creek nation, signed the Treaty of Indian Springs which agreed to cede all Lower Creek land to Georgia. Barnard opposed the treaty, and was one of the delegation that went to Washington to protest against its validity. Barnard then retired to his home near Fort Mitchell in present day Alabama. He was believed to have been about 60 at the time of his death. Andrew Jackson would later eulogize Barnard to his son, William: “A braver man than your father never lived.”

| BIRTH | |

|---|---|

| DEATH | unknown |

| BURIAL |

Fort Mitchell, Russell County, Alabama, USA |

Credit: Iola

Native American Bands Of Alabama:

Echola Cherokee

Ma-Chis Lower Creek

Mowa Band Choctaw

Principle Creek

Poarch Creek

Star Clan of Muskogee Creek

United Cherokee (Ani-Yum-Wiya Nation).

Cherokee Clans:

Wolf

Paint, Deer

Bird

Wild Potato

Long Hair

Blue

Native American Bands Of Alabama

Echola Cherokee, Ma-Chis Lower Creek, Mowa Band Choctaw, Principle Creek, Poarch Creek, Star Clan of Muskogee Creek, United Cherokee (Ani-Yum-Wiya Nation).

Cherokee Clans: Wolf, Paint, Deer, Bird, Wild Potato, Long Hair and Blue.

Tribes Recognized by the State of Alabama

Poarch Band of Creek Indians

Stephanie A. Bryan, Tribal Chair

5811 Jack Springs Road

Atmore, AL 36502

(251) 368-9136

www.poarchcreekindians.org

(Note: Also recognized by the Federal Government)

Echota Cherokee Tribe Of Alabama

Stanley Trimm, Chief

410 Main Street West

Glencoe, AL 35905

(256) 492-8678

E-Mail: stanleyandhelen@bellsouth.net

www.echotacherokeetribe.homestead.com

Cherokee Tribe Of Northeast Alabama

Stan Long, Chief

113 Parker Drive

Huntsville, AL 35811

(256) 426-6344

E-Mail: stan.long11@gmail.com

www.cherokeetribeofnortheastalabama.com

Ma-Chis Lower Creek Indian Tribe of Alabama

James Wright, Chief

64 Private Road 1312

Elba, AL 36323

(334) 897-2950

Fax: (334) 897-2950

E-Mail: chiefjames@centurytel.net

www.machistribe.net

Southeastern Mvskoke Nation

Ronnie F. Williams, Chief

208 Dale Circle

Midland City, AL 36350

(334) 983-3723

Cher-O-Creek Intra Tribal Indians

Violet Hamilton, Chief

1315 Northfield Circle

Dothan, AL 36303

(334) 596-4866

E-Mail: vlt_hamilton@yahoo.com

MOWA Band of Choctaw Indians

Lebaron Byrd, Chief

1080 Red Fox Road

Mount Vernon, AL 36560

(251) 829-5500

E-Mail: lebaronbyrd@aol.com

www.mowa-choctaw.com

Piqua Shawnee Tribe

Gary Hunt, Chief

4001 Evans Lane

Oxford, AL 36203

(256) 239-1523 or (256) 835-2110

E-Mail: morganandkaren@bellsouth.net

www.piquashawnee.com

United Cherokee

Ani-Yun-Wiya Nation

Judy Dixon, Chief

1531 Blount Ave or P.O. Box 754

Guntersville, AL 35976

(256) 582-2333

E-Mail: to ucanonline@bellsouth.net

www.air-corp.org

- Hodge, Frederick Webb. Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico. Washington D.C.:Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology, Bulletin #30 1907. Available online.

- Jump up ↑ Swanton John R. The Indian Tribes of North America. Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology, Bulletin #145 Available online.

3. Kan-hatki, Kealedji, Kolomi, Koasati, Muskogee, Okchai, Pakana, Wakokai, Wiwohka, where all subtribes branched from the Muskogee tribe which was apparently the most dominant tribe of Alabama. The Tukabahchee tribe was one of the four heads of the Muskogee’s.

Five Civilized Tribes

In 1830, the majority of the “Five Civilized Tribes” were:

1 Chickasaw Tribe

The Chickasaw had a few settlements in northwestern Alabama, part of which State was within their hunting territories. At one time they also had a town called Ooe-asa (Wǐ-aca) among the Upper Creeks.

2 Choctaw Tribe

This tribe hunted over and occupied, at least temporarily, parts of southwestern Alabama beyond the Tombigbee.

3 Creek Tribe (Muscogee)

When Alabama was first established as part of the Mississippi Territory in the early nineteenth century, the vast majority of the land belonged to the Creek Indian Confederacy, and most of the Native American towns in Alabama were inhabited by the Creeks. The Creek Nation was divided among the group known as the Upper Creeks, who occupied territory along the Coosa, Alabama, and Tallapoosa rivers in central Alabama, and the Lower Creeks, who occupied the areas along the lower Chattahoochee, Ocmulgee, and Flint rivers in southwestern Georgia.

4 Cherokee

Alabama became part of the Cherokee homeland only in the last quarter of the eighteenth century. Nevertheless, this population of Native Americans significantly contributed to the shaping of the state’s history. Their presence in Alabama resulted from a declaration of war against encroaching white settlers during the American Revolution era. A few decades later, the Cherokees served as valuable allies of the United States during the Creek War of 1813-14. Although the Cherokees fought alongside the United States under Gen. Andrew Jackson, he later campaigned for their removal from the Southeast.

Source: Encyclopediaofalabama

5 Seminole

The term “Seminole” is a derivative of “cimarron” which means “wild men” in Spanish. The original Seminoles were given this name because they were Indians who had escaped from slavery in the British-controlled northern colonies. They were actually Creeks, Indians of Muskogee derivation.