Cherokee Indians of Alabama

During the American Revolution, the Chickamauga, a pro-British faction of Cherokees, split from the Upper Towns on the Little Tennessee and Hiwassee Rivers in east Tennessee. Led by war chief Dragging Canoe and supported by British agents and sympathetic traders, the Chickamauga left to establish towns farther down the Tennessee River. Two of these, Long Island Town and Crow Town, were located on the river near present-day Bridgeport, Jackson County.

Some Cherokee worked their way down the Tennessee River as far as Muscle Shoals, constituting the Chickamauga band. They had settlements at Turkeytown on the Coosa, Willstown on Wills Creek, and Coldwater near Tuscumbia, occupied jointly with the Creeks and destroyed by the Whites in 1787.

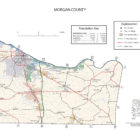

By 1782, the Cherokees had begun to establish settlements in what is now northeast Alabama in present-day Madison, Jackson, Marshall, DeKalb, Cherokee, and Etowah Counties and even as far west as Colbert County.

By 1800 many Cherokees lived on dispersed farmsteads in northeast Alabama. They established communities at Turkey Town, Wills Town, Sauta, Brooms Town, and Creek Path at Gunter’s Landing, all of which provided leadership within the Cherokee Nation.

Christian missionaries established schools at Creek Path (1820) and Wills Town (1823)

In 1806, as hunting declined among the Cherokees, the U.S. sought and won a land cession, significantly shrinking Cherokee land in Alabama by 1,602 square miles.

When war broke out in 1813, the Cherokees refused to join the faction of Creeks known as the Red Sticks, who were hostile to the United States. Instead, they fought alongside the Tennessee and U.S. troops under Andrew Jackson. Together they raided Creek villages along the Black Warrior River and fought in the November 1813 Battles of Tallushatchee and Talladega, from which they emerged victorious. Cherokee warriors played a major role in the attack on the Creeks of the Hillabee towns, who were members of the Red Stick faction. Following orders issued by Gen. John Cocke, the attacking party was unaware that the Hillabee had recently surrendered to Jackson. This one-sided assault became known as the Hillabee Massacre.

After American setbacks at the Battles of Emuckfaw and Enotachopco Creek in January 1814, the main Cherokee force joined Jackson for his assault on a large body of Red Sticks at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend on the Tallapoosa River in east-central Alabama on March 27, 1814. Here the Cherokees crossed the river and created a rear diversion. This unplanned but successful action allowed Jackson’s troops to make a frontal assault over a formidable defensive log barricade and resulted in the killing of approximately 800 Red Sticks. This outcome decisively ended the war.

Land Cessions

Cherokee Lands in Alabama

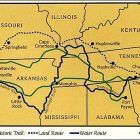

After the war, the U.S. government negotiated the Treaties of 1817 and 1819, which called for more Cherokee land cessions. Up to this time, the Chickasaw-Cherokee and the Cherokee-Creek boundary lines were not officially established. The United States paid the Chickasaws and the Cherokees, both allies during the late war, for lands north and south of the Tennessee River, as well as west of the Coosa River. Some Cherokees refused to leave their farms on ceded land and took advantage of a clause to claim private reserves. Most left their farms to relocate onto the shrinking tribal lands. Several hundred chose to journey across the Mississippi River to join the Old Settler Cherokees, a group that had emigrated prior to 1820.

In 1830, the federal government approved the Indian Removal Act, which required most eastern tribes to relinquish their lands and remove west to Indian Territory, now the state of Oklahoma. John Ross led the Cherokee Nation’s struggle to stay, taking the battle for sovereignty to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1832. Though the court ruled for the Cherokees, then-Pres. Andrew Jackson refused to enforce the decision and the forced removal of the Cherokees began in September 1838.