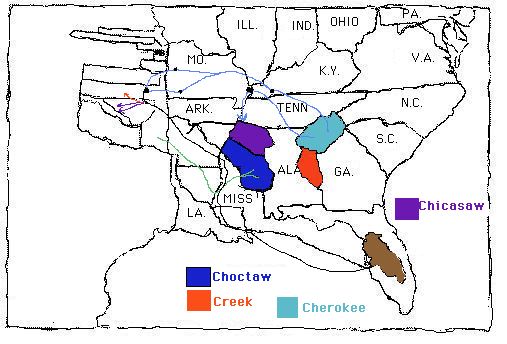

The US policy of discrimination against Native Americans was made official with the Indian Removal Act of 1830. It was the first time the United States government resorted to coercion, mostly in the cases of two tribes, The Cherokee and the Seminole, as means of securing compliance. The Removal Act was not in itself coercive, since it would only allow the president to negotiate with tribes that were long the East side of the Mississippi on a basis of payment for their lands. It called for improvements in the East and more land West of the Mississippi River. In carrying out the law, resistance was met with military force.

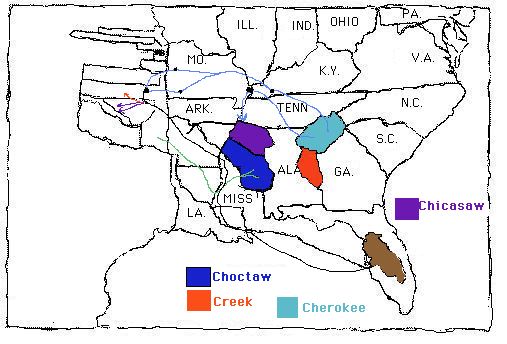

When Alabama was first established as part of the Mississippi Territory in the early nineteenth century, the vast majority of the land belonged to the Creek Indian Confederacy, and most of the Native American towns in Alabama were inhabited by the Creeks. These towns were significant political and tribal centers, but they were much more important as places of personal identity for the Native Americans who were born in them.

The Creek Nation was divided among the group known as the Upper Creeks, who occupied territory along the Coosa, Alabama, and Tallapoosa rivers in central Alabama, and the Lower Creeks, who occupied the areas along the lower Chattahoochee, Ocmulgee, and Flint rivers in southwestern Georgia.

Both groups resided in those areas from the early seventeenth century until the Indian removal era of the 1830s.

Creek Indian towns and settlement patterns were recorded in the accounts of travelers who visited them. Some early writers, such as James Adair, David Taitt, William Bartram, and Benjamin Hawkins, provided detailed accounts of what they witnessed when traveling through Creek territory.

The US policy of discrimination against Native Americans was made official with the Indian Removal Act of 1830. It was the first time the United States government resorted to coercion, mostly in the cases of two tribes, The Cherokee and the Seminole, as means of securing compliance. The Removal Act was not in itself coercive, since it would only allow the president to negotiate with tribes that were long the East side of the Mississippi on a basis of payment for their lands. It called for improvements in the East and more land West of the Mississippi River. In carrying out the law, resistance was met with military force.